Bethel awaits test results as questions arise over cancer trend

Marissa Gamache | News Editor

Tori Sundholm | Freelance

In 1972, Bethel College students marched five miles from the institution’s first erected buildings north on Snelling Ave. toward the future site of the college at 3900 Bethel Drive. Bethel first broke ground on the 3900 land in 1965, but buildings weren’t constructed until 1971. Soon enough, the Hagstrom Student Service Center opened and in the fall of 1972, Bethel welcomed the first batch of students to the serene new campus with sprawling grasses and Lake Valentine views.

Fast forward more than 40 years and thousands of students later, Bethel College is Bethel University – constructing multiple additions in order to accommodate a larger amount of students and provide advanced learning opportunities. Although they don’t all reside at the 3900 campus, Bethel is currently home to 6,000 undergraduate, graduate, seminary and adult program students and recently established the Wellness Center in 2015.

Throughout these changes, many of the first buildings constructed on the 3900 campus are still in use. The original Academic Center (AC) building, built in 1971-1972, has been linked to a concern by professors regarding a rising rate of cancer among Bethel faculty. At least five professors with offices and classrooms in the AC have been diagnosed with various forms of cancer.

Concerns from faculty regarding these health issues were raised at a faculty senate meeting in Nov. Professor Angela Sabates expressed concern over a possible relationship between the rising number of cancer cases in the AC building and its proximity to the science department.

The fact that the heating, ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in the science department had not been up to code in years’ past was a concern raised at the meeting in November. Administration made it clear at the meeting that the HVAC system has since been updated. Although HVAC concerns were remedied, concern over the true cause behind the statistic still resides.

“I think that we have a cluster of cancer among faculty at Bethel,” Professor Adam Johnson said, who is currently battling cancer. “The number of people who have cancer (or have died of cancer) is really improbable for a random event,” he added.

Due to the expressed concerns from faculty in regards to health issues and a possible correlation with environmental factors on the 3900 campus, Bethel administrators called on the services of Terracon, a consulting firm that provides environmental and facilities testing. Terracon’s first stage of testing focused on possible faults in the HVAC system, which came back clear according to administration at Bethel.

Terracon is now conducting its second stage of tests involving soil and water contamination testing on campus. Results will not be available until this summer.

Bethel acquired the 3900 property in mid 1960s from Dupont, then a 200-year-old chemical company that specialized in producing black powder and high explosives throughout the late 19th and early 20th century.

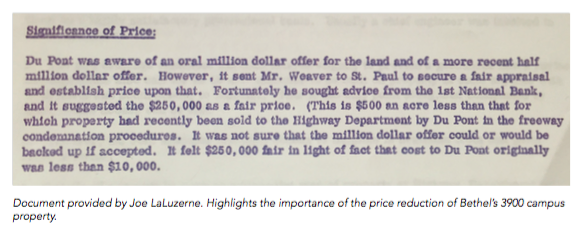

Bethel Magazine reported in its Summer 2012 issue that Dupont stored dynamite in bunkers across its 235 acres. According to the article, Bethel President Carl H. Lundquist asked Dupont to sell the land, but Dupont was hesitant to give up its dynamite holding grounds. Dupont eventually relented and sold the land to Bethel at one-fourth the price a development firm had previously offered.

The provisions behind Bethel’s acquisition of the property have been under speculation in the past, due to the sudden change in selling attitude of Dupont and the low price Bethel received.

Bethel had a long interest in the 3900 property due to its picturesque backdrop of Lake Valentine and the proximity to the original St. Paul location. 3M also had strong interest in the land for its Midwest Research Company, but due to Bethel’s long expressed interest, Bethel was given the first right of refusal from Dupont.

In a Sept. 1, 1961 document provided by Joe LaLuzerne, Bethel’s Senior VP of Strategic Planning and Operations, the initial proposal of Bethel’s acquisition of the 3900 campus are laid out by President Lundquist. The image below, taken from this document, describes the significance of the one-fourth price Bethel was offered.

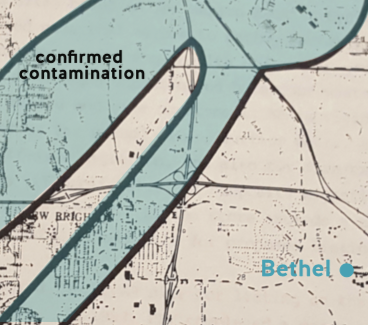

At the time of the property purchase, soil contamination issues at Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (TCAAP), 2.8 miles due north of 3900 campus, were unknown. Now, it is widely known that the ammunition plant, located in Arden Hills, dumped at least 10 recorded contaminants into nearby holding wells and ground pits in the area. The plant’s contamination started in the late 40s, and wastes are believed to have been disposed of improperly, according to the 1987 lawsuit filed by the state against the United States of America, the overseers of the TCAAP.

At the time of the property purchase, soil contamination issues at Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (TCAAP), 2.8 miles due north of 3900 campus, were unknown. Now, it is widely known that the ammunition plant, located in Arden Hills, dumped at least 10 recorded contaminants into nearby holding wells and ground pits in the area. The plant’s contamination started in the late 40s, and wastes are believed to have been disposed of improperly, according to the 1987 lawsuit filed by the state against the United States of America, the overseers of the TCAAP.

In May 1983, a southwest flow of water from the plant carried contaminants toward Long Lake. In the southwest corner of the affected area, four wells with more than 5,000 gas chromatography to mass spectrometry of trichloroethylene (TCE) were detected. From 1978 to September 1983, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency estimated that an excess of 18 sq. miles were affected and wells were contaminated with chlorinated hydrocarbon.

Studies conducted by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Minnesota Department of Health in the early ‘80s confirmed that there is low-level groundwater contamination of chlorinated hydrocarbons and TCE existing in five communities; Arden Hills, Mounds View, New Brighton, St. Anthony and Shoreview. Many of the wastes omitted from the ammunition plant are believed to have been contaminating the area for over 40 years.

In April 2013, Ramsey County purchased the 427 acre former ammunition plant from the U.S. Government. Demolition and cleanup were completed in November 2015 in order to meet residential standards. According to Ramsey County, crews removed approximately 100,000 tons of contaminated soil to meet residential standards.

In April 2013, Ramsey County purchased the 427 acre former ammunition plant from the U.S. Government. Demolition and cleanup were completed in November 2015 in order to meet residential standards. According to Ramsey County, crews removed approximately 100,000 tons of contaminated soil to meet residential standards.

According to a story published by the Star Tribune May 3 about the development of the area, Ramsey County hopes to construct a solar-powered eco-village on the ammunition plant’s former grounds that they hope becomes a national model for suburban development. Alatus LLC was recently chosen as the master developer for this plan, which is proposed to start in late 2017 or early 2018.

On Nov. 18, 2015, The Pioneer Press reported that Ramsey County asked authorities to “delist” the ammunition plant land for soil contamination that once was Minnesota’s largest Superfund. A Superfund is a United States federal law designed to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances and pollutants.

A May 3 report from United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), reports that contaminates of concern were detected in New Brighton, Arden Hills and the ammunition plant. The EPA has labeled these locations with contaminants of concern that pose an unacceptable risk to human health or the environment.

“Arden Hills made it very clear that their water was being drawn from groundwater and pumped from the Prairie du Chien aquifer, an aquifer that was named as a questionable water source in the late 80’s because of contamination. They were also unaware of testing for TCE, “We only test for what they [The Minnesota Health Department] tell us to,” an Arden Hills representative told us on the phone.

As of now, there is no known connection between explosives stored on the Dupont property, possible contaminants and cancer. The effects of soil contamination, especially TCE, caused by ammunition plant’s 40-year pollution dumping have also yet to yield any results, but Terracon’s second stage of testing may provide some answers.

“If we continue to have a high rate of cancer among faculty, then it’s much more probable that we have an environmental issue related to cancer,” Johnson said. “But we don’t yet have those data.”

Provost Deb Harless said Terracon is currently testing water samples on campus. The results will be available this summer.