The Bethel community responds to the fatal police shooting of Daunte Wright and the verdict of Derek Chauvin’s trial in collective dialogue and lament.

By Rachel Blood and Nate Eisenmann

Father, son and brother Daunte Wright was shot and killed by Brooklyn Center police officer Kimberly Potter April 11, just 10 miles from where Derek Chauvin sat on trial for the murder of George Floyd.

President Ross Allen addressed the tragic event in a Bethel community email April 13.

“Last Sunday’s police shooting of Daunte Wright—in the midst of the trial of Derek Chauvin, the tragedies that took place in Atlanta and Colorado, and so many other instances of violence—weighs heavily on the entire Bethel community,” he wrote. “We grieve for the friends and families of Daunte Wright and so many other individuals of color who face an increased risk of violence in our country.”

A Minneapolis jury convicted Chauvin on all charges in the death of Floyd April 20.

“While it cannot restore the life that was lost, this verdict is an important step toward the justice and reconciliation that we, as Christ-followers, seek,” Allen said.

Senior social work student Roland Osagiede grew up in Brooklyn Center. He was there last week for the protests happening in front of the police stations, directly across the street from where he attended high school.

Osagiede, who found out about Wright’s death via a phone call from his brother, did not personally know Wright, but knows a few people who did.

“The fact that this happened in my hometown is honestly very scary,” he said. “I have a lot of sadness, anger and fear in my heart. I easily could have been Daunte Wright, which is what is most scary. Daunte Wright could have been any one of my family members.”

Each day, Osagiede’s mother wakes up hoping not to see one of her sons dying on the news.

“If I’m being honest, I don’t feel safe in my neighborhood, and I’m sure many BIPOC families feel the same way,” Osagiede said. “I’m afraid to call the police for help because of what could happen. There is a huge disconnect between the police and people of color.”

Many of the police officers in Brooklyn Center live outside of the city, making it difficult for them to know and serve the community properly. Wright’s death lessened Osagiede’s trust in the Brooklyn Center Police even more.

Osagiede sees Wright’s death as a tragic accident that could and should have been prevented by Potter’s years of training and service. In similar situations with white people, he said, there seems to be more room for de escalation. He attributes the lack of deescalation to one thing: fear.

“I believe the officer made this mistake because she was nervous,” he said. “Why do you think she was nervous? I believe it’s because of the color of Daunte’s skin. I definitely understand that police officers have families that they want to make it home to every night, but something has to change.”

As members of the Bethel community come to terms with and process the reality of racism, Allen encourages all to engage in conversation with one another: RAs, RDs, student life staff, professors, friends or the Counseling or Christian Formation and Church Relations Offices. “My door—and my inbox—is always open,” Allen wrote.

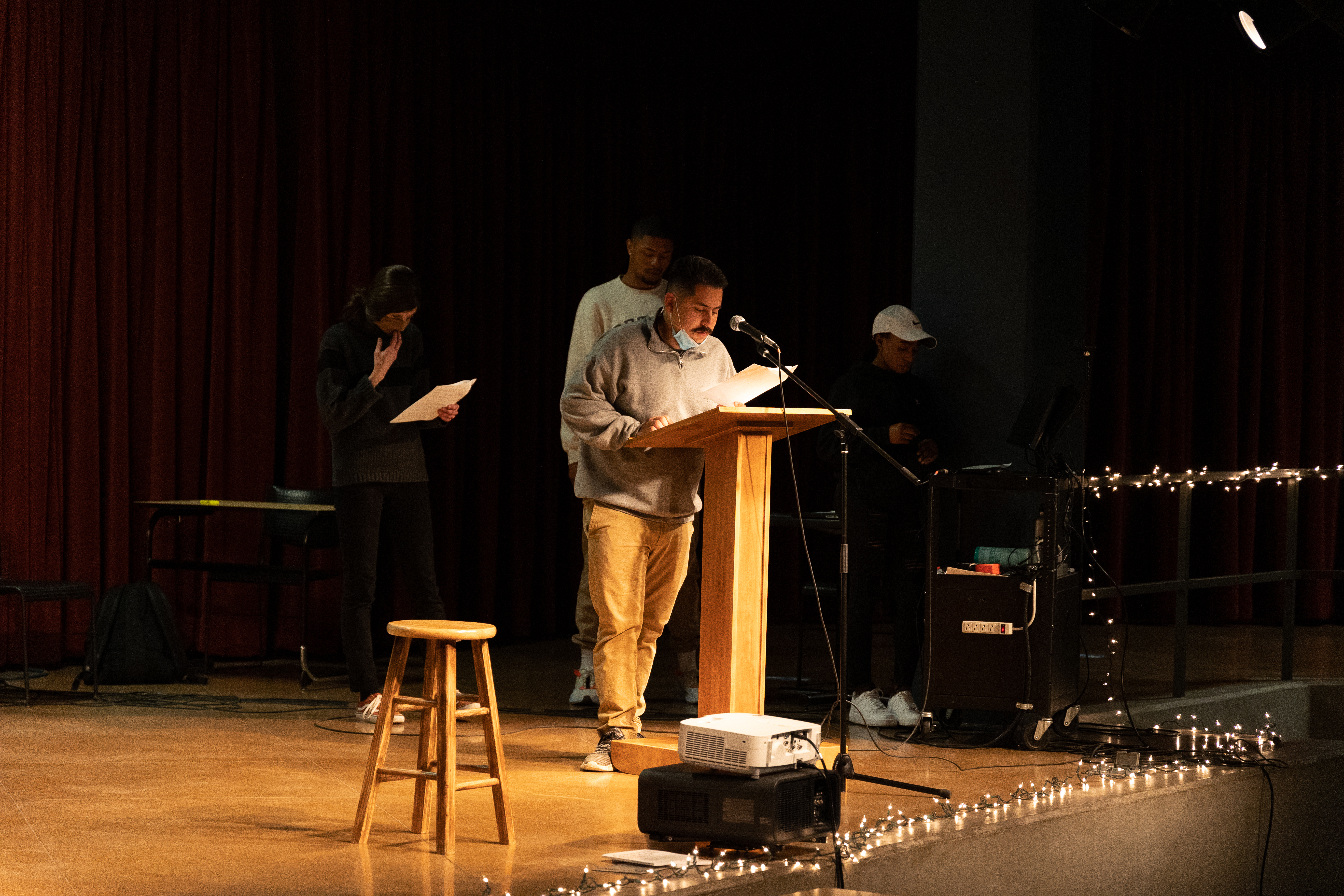

On April 21 at 9 p.m., just under 30 hours after the Chauvin verdict, students filed into the Underground for a “Liturgy of Lament,” a student-organized event focused on providing a space for attendees to express their feelings concerning the trial verdict and the death of Daunte Wright.

Senior Elizabeth Szilagyi, in collaboration with Adjunct Associate Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies Dale Durie, planned the liturgy, a customary practice in which Christians participate in a variety of kinds of worship such as prayer, scripture reading and reflection.

This particular liturgy involved the repetition of a reading from chapter five of the book of Amos; this passage is one of lament for the lack of social justice.

“I’ve been doing this for years and years. But I’ve never used a pure lament passage for [a liturgy],” Durie said.

Durie explained the flow of the liturgy in four steps. There would be a reading of the chosen passages, followed by a time for reflection on particular words and phrases that stood out to the participants. Next there was a time for writing down a prayer—any prayer that came to mind. Finally, there was a period of rest and for processing.

“Do not be a human doing, but a human being,” Durie said, in regards to the fourth step of the liturgy. He stressed the importance of staying focused on God and offering up any thoughts that came to mind. “There is permission to be angry…to be fully human in this moment,” he said.

For many students, the fourth part of the liturgy—rest and contemplation—was the most meaningful.

“I enjoyed the few minutes to just be,” sophomore Nancy Alquicira said.

Whatever emotion students felt throughout the night, Durie wanted to ensure that they would feel comfortable in that moment to work through what they were feeling.

“We’re all processing different things,” Durie said, “for some it’s [the pandemic], others it’s the trial or Daunte Wright. Hopefully it was an experience where God was meeting them where they were at.”