Victor Ezigbo knelt in front of the small bookshelf in his dorm at Wheaton College in Illinois, in awe of the technology and lineup of textbooks displayed before him. Growing up in Nigeria, Ezigbo had little to no access to educational resources due to the expensive nature of electronics and the scarcity of bookstores.

As a 24-year-old university student new to the United States in 2001, a simple trip to the library provided Ezigbo with answers capable of satisfying the questions that had been burning in his mind for years.

Why do humans suffer? What is the role of religion in modern society?

Kneeling on the floor, Ezigbo shut his eyes, bowed his head and spoke a prayer of gratefulness for all that had been provided for him. And then he asked for a gift.

“The gift was to be able to bring similar resources to the doorsteps of people who might not have the opportunity that I got,” Ezigbo said, “and God has answered that prayer.”

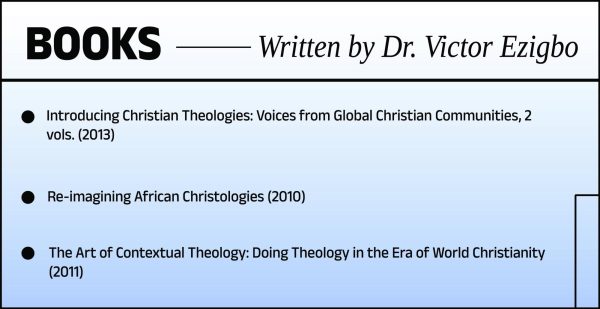

Before Ezigbo was a doctor, scholar and theologian, he was a pastor’s son of a poor family, a conflicted child and a firm believer in a God who provides. As a result of scholarships, donors and friends from church, Ezigbo received theology degrees from the Igbaja Seminary in Nigeria, Wheaton College in the U.S. and the University of Edinburgh in the U.K.

By 13, Ezigbo knew he wanted to study theology. He became fascinated with the power of prayer, coming from a family of eight that rose with the sun every morning between 5:30 and 6 a.m. for group prayer.

With a clear sense of direction and purpose for his future, one crucial question remained unanswered — How in the world was he going to pay for his education?

“I did something that I will discourage anybody from doing,” Ezigbo said. “I remember saying to God, ‘If you have called me to be a theologian, then you’re gonna have to pay for it.’”

Ezigbo wasn’t expecting it to work.

—

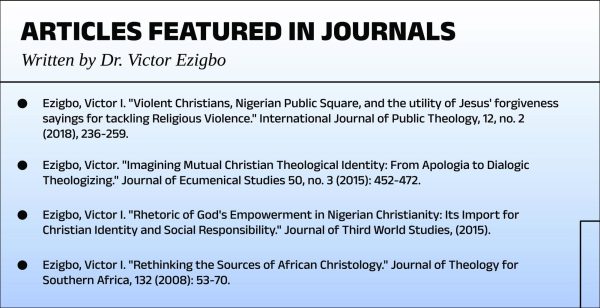

After studying Christian theology in three continents: Africa, North America and Europe, Ezigbo landed a position at Bethel University in 2008, teaching Biblical and Theological Studies.

At Bethel, Ezigbo says he teaches courses that encourage students to expand their worldviews, to understand socioeconomic structures and to participate actively in their local communities.

In his Biblical Theology of Poverty course last semester, Ezigbo provided his students with an opportunity to receive extra credit.

Undergraduate students Maddy Wilson, Drew Dunnwald and Isaac Lange piled into Wilson’s Jeep May 10. A 15-minute drive to Breaking Free, a women’s shelter in downtown St. Paul, revealed the harsh past and present reality lived out by many in their community.

Breaking Free provides housing, resources and support for survivors of sex trafficking and their children.

For nearly four hours, Wilson, Dunnwald, Lange and a handful of other students from Ezigbo’s class sorted through piles of donated clothing that engulfed a small garage on the property. Upon arrival, the walls and floor were virtually invisible due to the heaps of mismatched shoes, shelves of stacked clothes and loose articles of clothing in piles that hadn’t been touched in years.

Survivors and staff from Breaking Free floated in and out of the garage as the students cleaned and organized, sharing their stories and discussing the structural issues of poverty and human trafficking.

One woman was kidnapped from a bus station and sold into sexual slavery at age 14.

Another woman was forced to live on the streets and fend for herself at age 8 because there wasn’t enough money at home to support her.

Another woman’s mother offered her 7-year-old daughter’s body to men in exchange for services she could not afford, such as plumbing and electricity.

“I feel like you can kind of look down on these big issues and [think], ‘Oh, someone should fix that,’” Wilson said. “But we all have the agency and power to be able to take initiative in these situations.”

Wilson, a senior studying political science and reconciliation studies at Bethel, started working as an intern for Breaking Free last fall before she was hired as the administrative associate in charge of managing fundraising and donor engagement. For Wilson, taking time to learn the names, faces and stories of each survivor integrates faith into her work.

For Dunnwald, a junior business student at Bethel, placing himself in the survivor’s shoes for the day opened his eyes to the prevalence of poverty and trafficking in his local community.

“I just think times like this can open up your mind and [you] realize that there [are] a lot of things that need to be fixed in our society,” Dunnwald said. “You don’t really know what they need unless you actually step in and go do what we did.”

Lange, also a junior business major at Bethel, mentioned the structural aspect of poverty in the United States that leaves many individuals trapped in a vicious cycle of homelessness, trauma and abuse.

“For us, it may be easy to think, ‘I’ll just go out and get a job,’ when we already have the resources to do that,” Lange said. “Some people don’t have family members or a mom and dad who can help them in that aspect.”

—

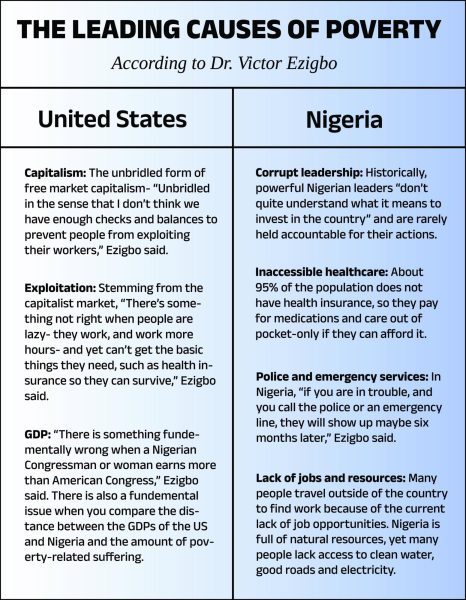

Back in the classroom, Ezigbo stressed the importance of understanding these global issues at their core, which are heavily influenced by the socioeconomic arrangements, political leadership and cultural influences embedded in each society.

Ezigbo has firsthand experience with the structural systems in three countries that both alleviate and contribute to the effects of poverty.

Take illness, for example:

In the United States, people must have good health insurance to receive care. Even with the purchase of an expensive care plan, any day a fluke accident can easily land someone buried under a mound of hospital bills.

When living in the United Kingdom, all Ezigbo had to do was show up at the general provider’s office to receive any essential medications or treatments. He didn’t even have to empty his pockets because of the free healthcare system in place.

Back in Nigeria, the first call when someone fell ill was not to the hospital or emergency line – they called the pastor.

“As a pastor’s kid, I can’t tell you how many times people would knock at our door, sometimes at midnight, because they wanted the pastor to pray for them,” Ezigbo said. “If you’re ill in Nigeria, you pay out of pocket.”

Lacking the necessary resources to pay for care upfront, many people in Ezigbo’s community turned to his father for guidance, placing their lives in God’s hands.

Ezigbo, too, placed the course of his future in the hands of the heavens. His prayers were heard, doors were opened and money came from nowhere, allowing Ezigbo to share his knowledge and faith with the world.

“I believe that the best gift my parents gave to all of us, their kids, was to introduce us to Christ,” Ezigbo said. “That for me [was worth] more than anything else they could have given to us.”