I looked over my schedule one more time, mapping out which door I’d use to get into the building and which elevator could get me to each of my classes.

My first class was Monday at 9 a.m. in RC403.

OK, so I’ll go in through the Robertson Center on the second floor. I’ll take the elevator to the right of the athletic trainer’s room. Perfect.

Until it wasn’t perfect.

“Out of order” read a sign on the front of the steel door.

I felt my face start to get warm. I panicked inside. I have to take the stairs.

–

Before having surgery, I never considered how students with physical disabilities navigate Bethel’s campus. A lack of automatic doors or ramps or out-of-order elevators didn’t matter to me. Because I didn’t need them.

Now that I’ve been on crutches for the past seven weeks, I realize just how naive I was. I was prepared to be slower and a little sore under my armpits. I was not ready to go up three flights of stairs to get to my 9 a.m. strategic social media class on the fourth floor of HC, to have to ask for help when I was clearly struggling to open a classroom door and to give students and faculty permission to pass me because I was going too slow.

It didn’t take long for me to notice that there were a number of students, mostly athletes, who were injured and on crutches, in a boot or using a scooter.

I thought to myself, “What would I do if I was more restricted or if I was in a wheelchair?”

I knew I wasn’t the only one being affected.

Students like Ashton Lafleur and Natalie Henneberg are accustomed to dealing with these issues.

After experiencing a birth injury and undergoing multiple surgeries, first-year student in the BUILD program Lafleur was left with little mobility in his legs. To get around campus more efficiently, he uses a walker or a wheelchair. The most difficult part for him is desiring to be independent, but having to ask for help when he needs it.

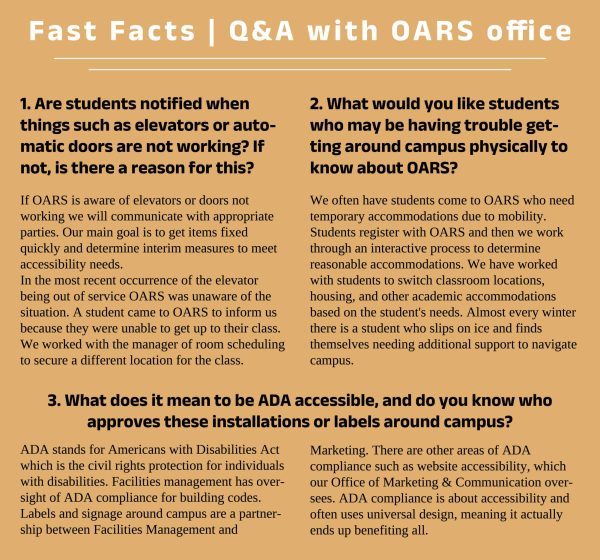

“I know I need help, so I ask for it, but at the same time, it’s just frustrating knowing that I can do it without help but need help because something is out of order,” said Lafleur. “That’s the most frustrating part of it.”

So when the automatic doors going into the BAC only open halfway and he can’t fit his walker all the way through, he is either forced to ask someone to help him open it all the way or he “bulldozes through it.” Or when he needs to go to IT to get apps downloaded on his iPad but can’t get to the fourth floor, he has to have someone else go up for him.

Since Nelson Hall is the only freshman dorm with an elevator, Lafleur didn’t have a choice in where he would live for his first year on Bethel’s campus.

Lafleur was placed on the third floor, and the laundry room is on the first floor. When the power went out across campus a little over a month ago, Lafleur found himself stuck on the third floor, forcing him to trek down the stairs, using the railing as support, while another student carried his walker down three flights of stairs.

And when Henneberg was deciding where she would live this year, she was left with two choices: live in a freshman dorm as a senior, or live in Heritage like she did last year. Instead, she decided to live at home.

Despite being used to navigating different spaces, both ADA-accessible and not, Lafleur says when he chose to come to Bethel, he was under the impression that his accommodations would be met and that he’d be able to get from class to class every day comfortably.

For Henneberg, who has been using a wheelchair for two years, Bethel was a dream come true in comparison to the University of Northwestern – St. Paul, where she transferred from in 2021. She attended her first year of college remotely due to COVID-19, and when orientation came around the next year, she learned there was only one elevator she could use.

Bethel had an elevator in every building, automatic doors going in and out, and it felt like home.

There are plenty of little annoyances that Henneberg can put up with – uneven bricks on the pathway from the CC building to the HC building, tables surrounded with chairs leaving no room for her and science lab counters being too high for her reach. But this year was the first year Henneberg thought, “OK, this isn’t working.”

One of Henneberg’s classes was on the fourth floor of the HC, but because the only elevator to get to that floor was out of order, she had to go to the Office of Accessibility Resources and Services to get her schedule changed. The office said it was unaware of the situation, and when the power went out Henneberg was forced to attend class via Zoom.

Luckily for me, my limitations are only temporary. I could handle taking the stairs one at a time at the pace of a snail on crutches until the elevator was back up and running.

Henneberg says she can make most things work. Her main concern is for the students who will come after.

“As someone who has worked in admissions, I want to be able to tell prospective students that they should come here whether they’re in a wheelchair or not,” Henneberg said. “Right now, I don’t feel like I can do that.”

Henneberg wants to encourage students and faculty to be more aware of students with disabilities and take small steps such as always having at least one opening around a table, or moving a chair from a desk. In the neuroscience lab, there is a chair removed from the desk she normally sits at.

“This means a lot to me, and it’s a very small gesture,” Henneberg said.

After nearly two months of physical therapy, I can now walk around with just one crutch in an unlocked brace. Opening doors and holding things in my hand feels like more of a blessing than ever before. In six weeks I’ll be able to take the stairs unassisted and return to more normal activities like walking on the treadmill and weight lifting.

I know my frustrations are temporary, but my awareness is not. Now, when I walk into a room with chairs surrounding every table, when I feel the rough tile underneath my feet or when I see that an automatic door or elevator isn’t working, I’ll think of Henneberg and Lafleur, and other students who deal with these frustrations for life.