Bethel alum Tu Lor Eh Paw sits on the small, wooden stage with seven younger girls, their voices echoing throughout the mural-painted walls as they sing along to Bruno Mars’ “Grenade.” As program director at The Urban Village, Eh Paw runs karaoke tonight by connecting her phone to the bluetooth speakers and playing songs that the teenage girls can’t help but sing along to.

Across the room teens giggle with one another, relaxing on couches or playing guitar. Adidas backpacks, The North Face winter coats and Nike shoes lay scattered and forgotten as everyone settles down from the fun-filled hours of The Village Klub, an event held every Tuesday and Thursday evening including sharing of a Thai meal, activities like cup stacking contests and a rock-paper-scissors tournament.

The Urban Village was founded in 2019 by Jesse Phenow and Ku Hser.

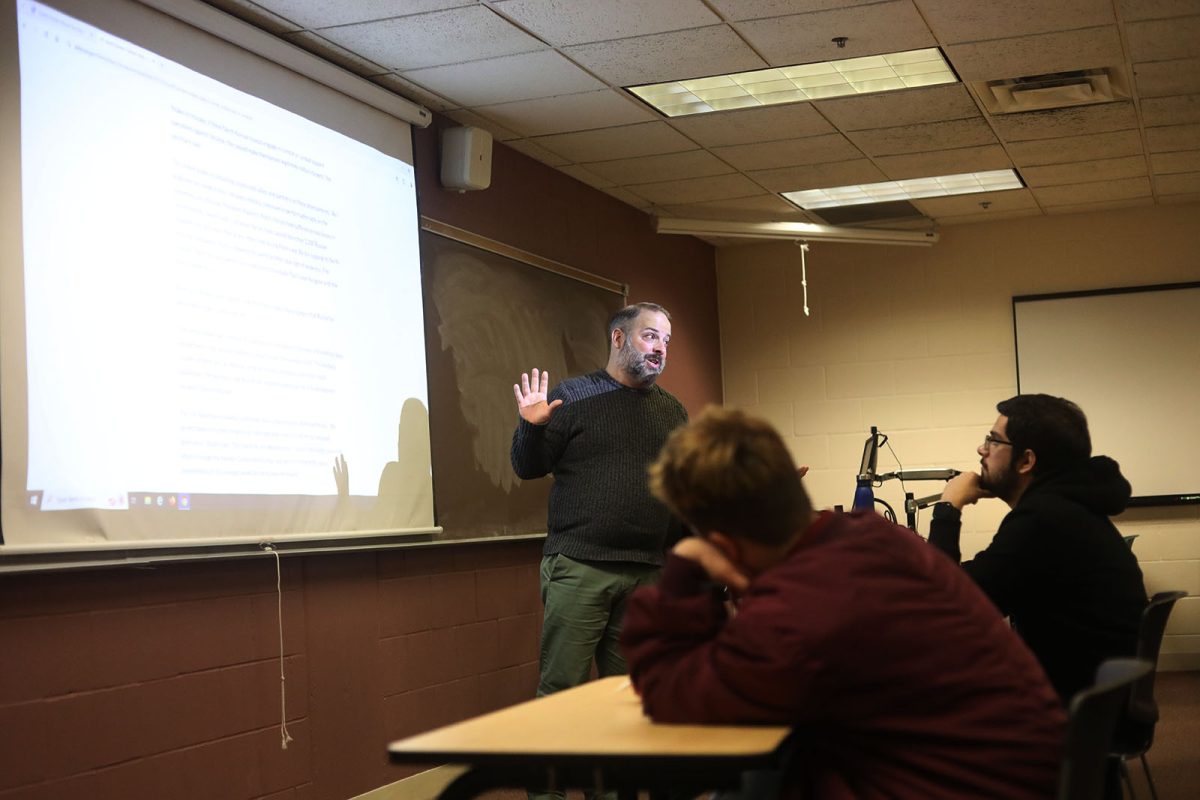

Phenow, a 2014 Bethel University graduate, started volunteering with K’nyaw refugees who resettled in the Twin Cities in 2011 as a requirement for his reconciliation studies major, which no longer exists. Communications professor Ripley Smith paired him with a family with seven young boys, all under the age of ten. Phenow started volunteering with a sense of pride, expecting that he was going to be someone who would provide help to a family in need and bring the United States to them. But their first interaction left him “rattled.”

“They flew open the doors and welcomed me in,” Phenow said. “I thought that I was showing up to their apartment to welcome them to the United States. And what I found out is that actually, they were welcoming me.”

The troubling narrative of white Christians going into a community of color and saving them through their good work diminished for Phenow when he realized they did not need to be saved.

Phenow eventually saw volunteering as more of a partnership and even moved into a house with his first client family. The family invited him to the hospital when its youngest son joined the world. And many members of the family were groomsmen in his wedding.

As Phenow became closer with the K’nyaw community, he realized there was no space that they could call their own, despite Minnesota being home to one of the largest K’nyaw communities in America. More than 17,000 K’nyaw people have resettled in St. Paul since the early 2000s.

So when Phenow’s friends from Bethel started hanging out with people from the K’nyaw community, they became inspired by Phenow’s new relationships. Many people became connected to the work Phenow and his friends were doing, eventually leading them to donate a building where Phenow and his friends could continue to hang out and do volunteer work while welcoming the community around them.

Original art made from local K’nyaw artists covers the walls. Mannequins wearing colorful traditional clothing can be seen through the large windows. There’s a kitchen for cooking food, something K’nyaw value in their culture. Bits and pieces of history can be found in books, pictures and maps spread all throughout the building.

“My life has been so transformed. Like I have a community where I have belonging,” Phenow said. “I have friends that would, you know, go to war for me. And those are things that, no matter what The [Urban] Village does, or no matter what I do as an individual, I’ll never be able to repay that debt.”

Among the youth attending The Village Klub, many were born in Myanmar and have memories of violence and displacement. Myanmar is a diverse country, with the state recognizing more than 100 ethnic groups. Roughly two-thirds of the population are ethnic Burmans, who have enjoyed privileged places in society while many ethnic minorities have faced systemic discrimination. This oppression has led to what some analysts describe as the world’s longest continuing civil war. Due to ethnic and religious persecution, many K’nyaw families were forced out of their homes and sought shelter in Thai refugee camps.

This trauma, generational or firsthand, sticks with many of the people involved with The Urban Village. But the nonprofit workers try to help – not by telling children what they need to do, but by creating an environment where they can stand in solidarity and provide programs to aid their journey of healing. One such program is Asian Youth Outreach, a one-on-one mentorship program where youth are connected with a trained and trauma-informed K’nyaw mentor. Another is Karenni Camp, a summer camp experience focused on cultural immersion. Various community events and festivals that students can help plan take place throughout the year.

Along with free tutoring, potluck meals and “Minute to Win it” competitions, these events draw dozens of K’nyaw children through the nonprofit’s doors.

The Urban Village also partners with Bethel to provide the Fight for Something Scholarship, which gives K’nyaw youth the chance to further their education at Bethel, preparing them for the change they want to make toward the crisis happening in their home country.

“We believe that this generation of the diasporas is going to participate in a brighter future for their homeland,” Phenow said. “We want to accompany them as they launch into that work.”

Three freshmen at Bethel were awarded the Fight for Something Scholarship this year and are working toward making a change in their community and home country.

Psychology major Nay Seya hopes to help others going through mental health struggles similar to those he experienced after being born in a refugee camp in Thailand. Seya has lived in Rhode Island, Indiana, Texas and now Minnesota, causing him to never feel connected to his culture. The Urban Village has helped him get closer to his community, which according to Seya, he wouldn’t have done otherwise.

Resettling in Minnesota in 2007, and the first person to go to college in her family, nursing student Hser Thaw wants to return to Thailand, using her skills to provide medical assistance to those in need in refugee camps.

“I just want other students to know that they have an opportunity like we do and that there’s people like Urban Village helping them out,” Thaw said.

And after getting involved through The Urban Village in high school and seeing the impact the organization has made, freshman Htee Moo became inspired to major in political science.

“I want to go back [to Thailand and Myanmar], I want to be involved in the Karen community, I want to help out. I just want to give back to the people,” Moo said.

Along with the scholarship, The Urban Village and Bethel have worked together on events on campus with the goal of helping the community share their stories and culture and raise money for those in need back home.

“I feel like we do have a small Karen community,” senior Htoo Paw said. “But when we plan something with Urban Village, it really helps us to bring us all together and make events happen.”

Before starting work at The Urban Village in January 2022, Eh Paw, a refugee from Thailand, graduated with a business and marketing degree. She could be working for a corporate company or doing something to benefit herself, but that’s not where her heart is – instead, she finds fulfillment by standing with the marginalized and giving back to her community.

“I truly believe that God put me where I need to be so that I can be the example that the [K’nyaw] community needs,” Eh Paw said. This is why she can be found twice a week scrolling through her phone for the next karaoke song at The Village Klub.

“Okay, guys!” her voice booms out of the speaker. “This next song is a special song about a guy missing his loved one who he’s lost!”

The girls surrounding her giggle as she presses play. Soon she and the other girls sing Austin Mahone’s “All I Ever Need” loud in Karen, a language from home.

![Tu Lor Eh Paw and other teenage girls sing Bruno Mars’ “Grenade” during karaoke at Urban Village Klub after a fun-filled evening of food and playing “Minute to Win It” games at The Urban Village Nov. 9. “[The Urban Village’s] focus is to accompany K’nyaw and Karenni youth as they connect, heal and launch,” co-founder Jesse Phenow said.](https://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-20-at-9.13.11-PM-1200x797.png)