Trent Viesselman faced an early October snow behind Lissner Hall, digging through drifts and fighting the wind to find the neon pink markers driven into the ground.

Vivian Marchan looked over her shoulder in the woods after hearing a rustling. When she turned around, a deer was following her.

Cady Peterson spent many hours sporting chest-high waders, beating away branches and practically crawling through shrubbery.

All of this to count the buckthorn that grows on Bethel University’s campus stem by stem.

Visesselman, Marchan and Peterson are among the students who have been a part of researching not just the buckthorn on campus, but the goats that eat it too. It’s true — the “Bethel goats” are not simply a randomly appearing petting-zoo-like attraction — but instead part of the efforts to protect the native plants on campus.

The three students’ research each take different directions, but they all have a common goal: learn more about the invasive buckthorn species and find a way to stop the spread.

“It just loves to grow,” Marchan said. “It loves to kick out our native foliage by just taking that space.”

Buckthorn was originally brought to the United States from Eurasia in the nineteenth century as a good option for home gardens because of its height and density. But what was intended to be a beautiful landscaping plant quickly spread across the continent, taking out native plants along the way.

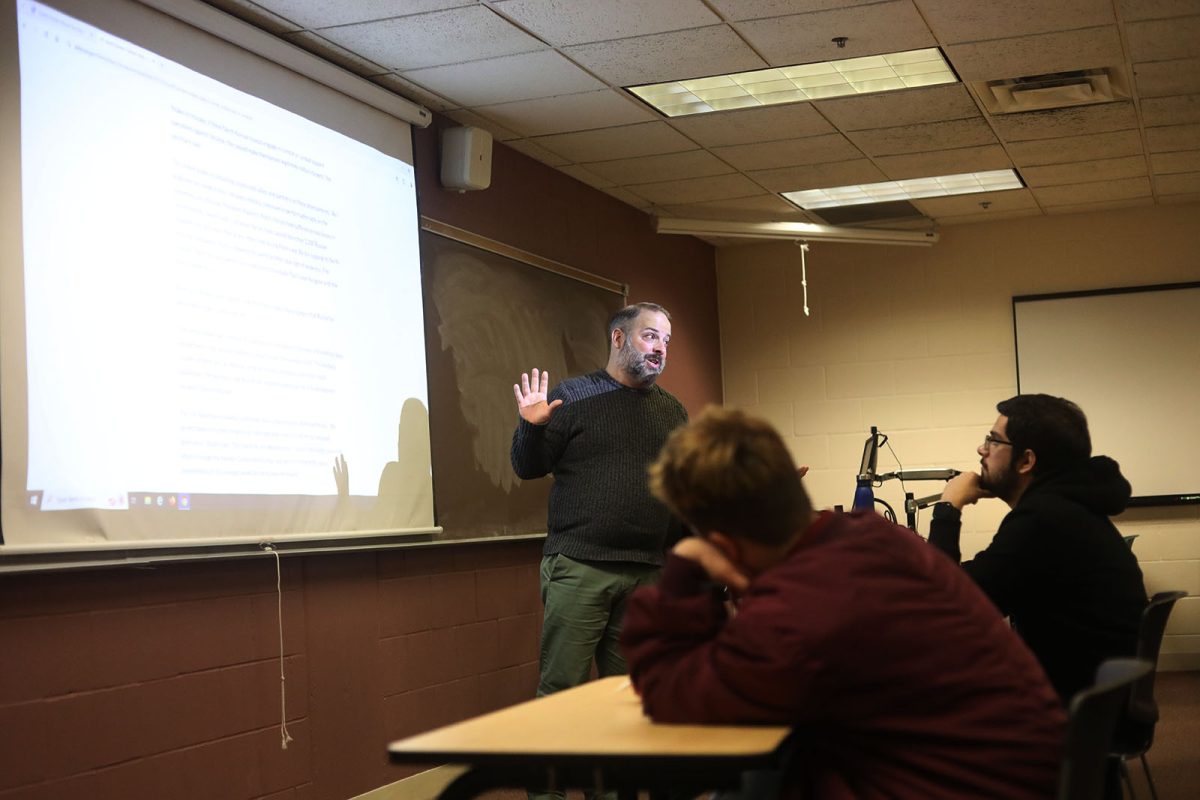

With a desire to learn more about invasive species and how to control them, Peterson signed up to conduct research this fall under the direction of Professor of Biological Sciences Sara Wyse. She began her research in the Lakeside Plot, the area of woods between the Lakeside Center and Lake Valentine. Here, and in each of the three plots around Bethel’s campus, there are 40 randomly placed stakes. The plot is divided in two: a section plot where the goats are allowed to graze and a control, a section where the goats don’t go.

Peterson created meter-by-meter quadrants with PVC pipe between the neon stakes where she could then individually count each stem of buckthorn, categorizing them into three groups by size. After collecting the data, Peterson looked over past years of data and concluded what effect the goats have on the growth and height of buckthorn. While the research endeavor sounded easy enough on paper, the execution was a straining process that involved hours in the elements, collecting data.

The senior biochemistry major looked at the chlorophyll content in buckthorn as a proxy for nitrogen content and used dry mass to find the carbon content. Marchan then compared the nitrogen and carbon contents and analyzed it in response to the goat grazing, learning along the way good methods for getting all of the chlorophyll out of the leaves. Starting in summer 2022, Marchan wanted to know: “Are these plants investing more nitrogen or depleting their nitrogen resources in response to grazing?”

After the first grazing session in early summer, the buckthorn plants were investing more nitrogen. Because of this, they seemed to have depleted themselves of their nitrogen resources, being unable to respond as well during the second graze later that summer.

“It seems that the grazing depleted its nitrogen resources and put the plant in a position of stress where it was unable to adequately respond with that nitrogen reflux for stressors that happened later in the season,” Marchan said.

On top of the stress put on the plants in this one season, the goat’s grazing may have larger benefits to helping control the invasive species, as buckthorn is typically the last plant to drop its leaves. With a lack of necessary nitrogen after grazing, buckthorn may not have the advantage over native foliage in having a longer growing season.

Because of the results of her research, Marchan published her paper to Spark Journal, a place where Bethel’s various departments can submit papers and projects to be published through the Bethel library.

Other students, like environmental science major Viesselman, focused on other specific areas. Viesselman looked at the impact the goats were having on woody, native species. While the goat’s job is to eat buckthorn, if they are hurting the native foliage, they are doing more harm than good.

“We’re taking the data that we’ve gathered for all these months, and we’re saying, ‘Here’s what we did, this is what it is and here’s how we can apply this for future years,’” Viesselman said.

Before a conclusion can be made, though, there are hours of labor put in.

“I do have to say research is way more fun when you have someone to do it with,” Marchan said. “That camaraderie is something I really value and I’m really thankful that I had someone as amazing as Cady to do research with.”

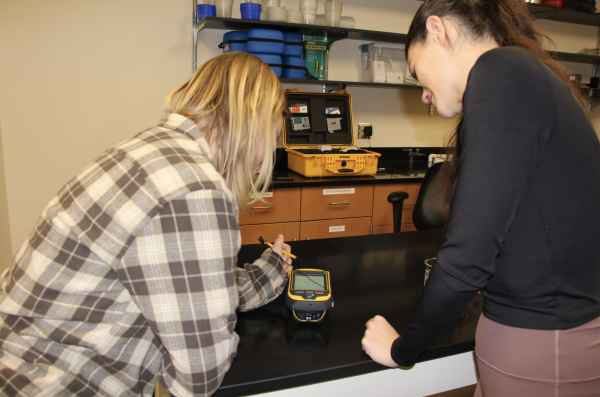

Both Marchan and Peterson attribute the positive memories of researching to being with good company and celebrating little wins, like the day they finally figured out how to use the Trimble system to collect data.

“A lot of people are like, ‘Oh, the goats are on campus,’ and they get so excited, but people obviously don’t know the reasons behind it,” Peterson said.

Peterson and Viesselman will present their findings at a symposium before the end of the year, and another round of research will start in the warm months of 2024. Come spring, the goats will be back on campus.