Editor’s note: This story mentions an eating disorder.

Danielle Buckenmeyer turned to her desk neighbor Jonah at the prompt of their seventh-grade teacher. It was a Monday, and they were told to share what they did over the weekend.

“I went to church yesterday,” Jonah said.

A simple statement, but Buckenmeyer didn’t believe him.

“I laughed and was like, ‘What? That’s not real,’” Buckenmeyer said. “‘You know that’s just in movies.’”

But in an atheist household in downtown Portland, Oregon – the 13th most unchurched city in America according to a national survey conducted by an evangelical polling firm – Buckenmeyer didn’t know any better.

Buckenmeyer, a freshman relational communications major with a minor in social welfare studies at Bethel University, battled anorexia in middle school. After the eating disorder hospitalized her and nearly took her life, Buckenmeyer wrestled with questions that, up to that point, she felt were unanswered.

Why am I going to fight to get better? What is there to fight for?

After an initial stint in the emergency room until she regained strength, Buckenmeyer spent a year in treatment, where she made a full recovery. But her existential questions lingered. Buckenmeyer figured maybe people like Jonah – church-goers – might have it figured out.

She first sought answers at a Catholic mass, but felt rejected when it was time to take communion. The Catholic church only allows members to receive the Eucharist. Buckenmeyer didn’t know this until the priest gave her a blessing instead of bread.

Her first church experience didn’t provide her with comfort, nor did it satisfy her questions. Buckenmeyer thought maybe people like her parents – atheists – might be right about religion. She put her questions to rest for a time. But when COVID-19 put her city on lockdown, sending everyone home to isolation, the questions began again. Initially, Buckenmeyer thought the quarantine would last just a couple of weeks, not months.

Lacking a belief that anyone or anything was in control of the world, Buckenmeyer sought control for herself, initially through a rigorous restriction on her diet and later in her popularity status at high school. When COVID took her social life away, she once again had nothing to fill the “void” in her soul.

While she said she didn’t want to die, she still felt there was no point to living.

“We’re just existing on a floating rock that’s gonna eventually blow up,” Buckenmeyer said. “That’s how it is if there is no God.”

Buckenmeyer knew that even if the world went back to normal, the value she found in her popularity among others would still be temporary.

Finally, Buckenmeyer had an experience she described as “Pentecostal.” Two months after the pandemic hit, she sat alone in her bed at 2 a.m., unable to sleep. She wrestled with her hopeless thoughts, as was the case many nights prior. A tingling sensation came over her, and in one life-changing moment she felt overwhelmed with “the fruits of the Spirit.”

“It was like the presence of God just came on me in one moment. And I was like, ‘God loves me and God sees me,’” she said. “Later, when I read the book of Acts, I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, these people had the same experience.’”

She got connected with Mosaic Church, a nearby non-denominational congregation, over Zoom and was baptized in September 2020. The first virtual youth group she attended was about the fruits of the Spirit, which finally gave her some answers after her Pentecostal moment.

“Nothing else has worked, [and] God is pursuing me,” Buckenmeyer said. “God wants to know me, so I’m going all in.”

Buckenmeyer’s parents were always supportive of their children being independent in their beliefs, so they had no fear of letting Buckenmeyer explore the answers she was looking for. Buckenmeyer admits, however, that they didn’t think any of her answers would come from Christianity.

But as she openly professed her faith – reposting Bible verses on Instagram, sending scripture in the class Zoom chat and speaking up during a pro-premarital sex health class – Buckenmeyer began to receive death threats from peers at Grant High School.

Her best friend since kindergarten at the time ended their friendship at the news that Buckenmeyer was getting baptized. Buckenmeyer transferred to a Christian high school in Portland for her safety.

At home, her parents and older sister initially struggled to take the news of her faith.

Theological conversations became regular most nights in the Buckenmeyer household, and as the topics grew deeper each night, Buckenmeyer says her family began to feel more attacked by her shifting values.

At its worst, the conflict resulted in her older sister deciding to end the relationship with Buckenmeyer. Her parents eventually became more accepting and even proud of Buckenmeyer’s beliefs.

“I wouldn’t want it any other way that she would feel confident enough and comfortable enough to differentiate herself from us,” Buckenmeyer’s father, Marty, said. “As a parent… I want my kids to be who they are authentically in the world.”

Buckenmeyer discovered Bethel through a college fair at her new Christian school. She considered going to a public college, where she felt the Gospel was more needed, but eventually decided to come to Minnesota.

Bethel students belong to over 30 Christian denominations, according to Bethel’s Office of Spiritual Formation and Care. Despite this, among many of the students walking around the “Bethel Bubble” and participating in classes with “Bible thumpers” are those, like Buckenmeyer, who had no Christian backgrounds in their homes.

Like Buckenmeyer, Aaron Smallman and Claire Carlson found faith outside of their families. Each also admits they, at times, felt like an outsider coming to a Christian university.

Other Bethel students grew up going to church on Sundays. They know every song in the hymnal and made friendship bracelets at Bible camp. They know how David killed Goliath and how Daniel survived the lion’s den.

“A lot of people who grew up in Christian homes kind of naturally had [Bible knowledge] … in their developmental stages, while I had to learn it on my own,” Smallman said. “VeggieTales doesn’t come naturally to me.”

—

Carlson’s journey to faith began in elementary school when her third grade teacher invited her class to go to Grindstone Bible Camp. Naturally, as a third grader, this piqued Carlson’s interest and she went with a group of friends.

“I went to camp for the first time and I absolutely just loved and adored every second of it,” Carlson said. “My counselors were so cool and games were so fun and the snacks at the canteen were just, like, divine in my brain.”

Raised by parents who experienced religious trauma in their earlier years, Carlson, a sophomore art therapy and missional ministries double major, was never exposed to any form of religion until attending summer camp. However, her parents made it clear that they would be supportive of any decision their daughter made regarding spirituality.

Carlson continued to love the games and friends and food, but it wasn’t until later that she realized the value of camp.

“I soon realized that I had such a passion for camp ministry because I knew how impactful my connections with my counselors were that I wanted to be that,” Carlson said. “Like, I can be that person for another person. I took that opportunity and I ran with it.”

When Carlson was 13, the focus of the summer was James 1 and counting trials as joy. The campers learned that Jesus never promised it would be easy, and after meditating on this scripture for those two weeks, Carlson returned home.

She was welcomed with the news of her parent’s divorce.

“From the minute I found out they were getting divorced, I was like, ‘There are gonna be kids that I get to tell about Jesus because their parents are getting divorced,’” Carlson said. “It blows my mind to think about it now that God so powerfully worked in my life and I cannot explain the faith that I had when I was 13 years old.”

In a non-Christian home, Carlson had to look to someone other than her parents for guidance in her walk with Jesus. Megan Brunner, a high schooler from Carlson’s youth group, was that person for Carlson. Brunner is like a “big sister” to Carlson, investing in her and her faith.

“I think she saw me like how Christ saw me, which was the first time that I had had that in my life really consistently,” Carlson said. “She was the kind of person that invited me over and taught me about theology.”

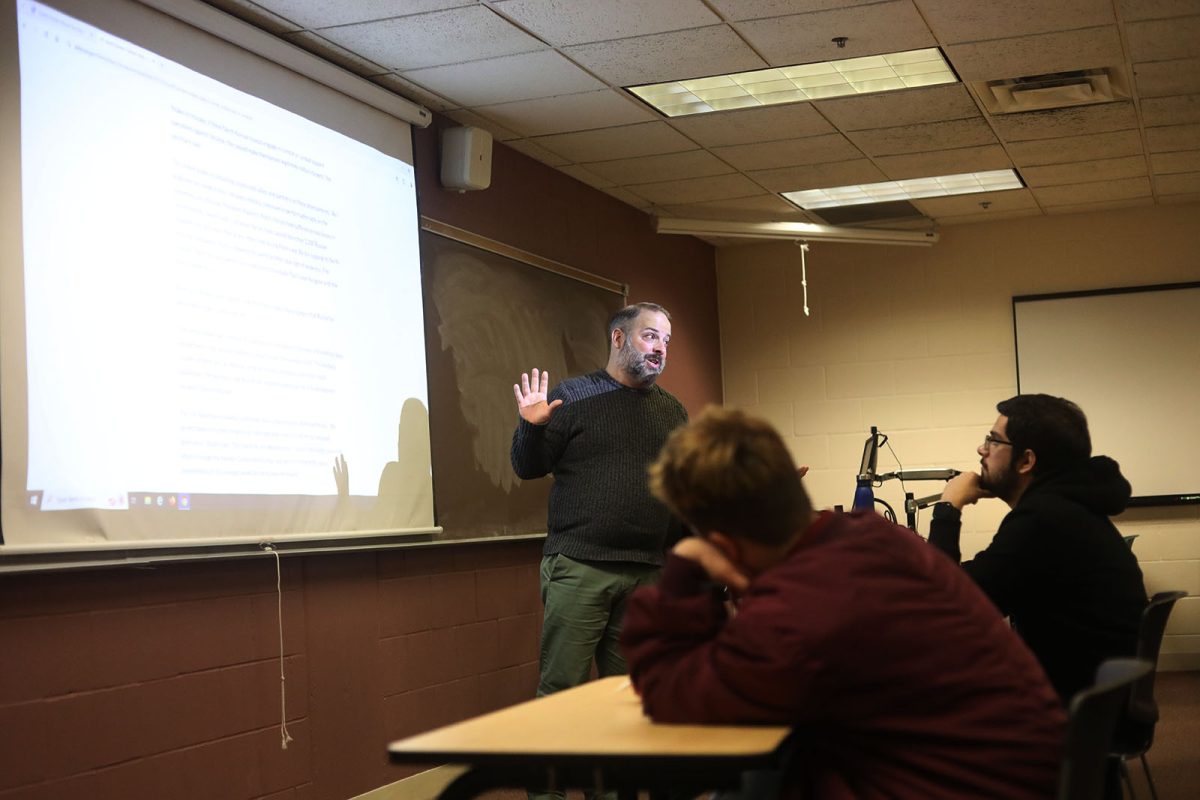

At Bethel, Matt Runion leads the Office of Spiritual Formation and Care – a position he’s held for 24 years. Due to the spiritual diversity of Bethel’s student body, Runion aims to make his reach adaptable to any background, both for those baptized as infants and those who may have little experience in a Christian environment.

“A really important part of our ministry is creating spaces where people can ask hard questions,” Runion said. “Where curiosity is celebrated and doubts can be spoken and explored.”

One way Runion has adapted to a diversity of faith backgrounds is through the creation of bookmarks which describe different methods to study scripture that work for different learning styles, values and interests.

One is inspired by Christian author Priscilla Shire, a member of the Church of God and Christ denomination. Another is from Lectio Divina, or “divine reading,” typically used by the Catholic church as early as the fourth century. Another utilizes Martin Luther’s approach.

“We’re trying to create a way for students to see themselves, so if a Lutheran student were to walk in and look for Bible study resources… they would find something,” Runion said. “But I do think that it’s really valuable when the students step out of their familiar traditions and they try other ways of living out their faith.”

—

Smallman, a junior communication studies and media production double major, was raised in Minneapolis in a single-parent household where there was no conversation of religion. He doesn’t remember hearing the name of Jesus as a kid. Growing up in a broken home, Smallman encountered abuse at a young age. He feels that his upbringing forced him to mature sooner than many of his peers.

“I saw my friends growing up have all these put-together families,” Smallman said. “And I reflected on mine … it was not the same at all.”

As Smallman entered high school, the feelings of loneliness and brokenness weighed on him. He attended church a handful of times, joining his friends when they extended the invite. High school also brought his first experience with prayer – his friend’s family saying grace before dinner.

On the way to a movie during his sophomore year of high school, Smallman saw a “cool-looking building,” which was the home of River Valley Church Crosstown Campus in Minnetonka. He decided to attend River Valley and the very first sermon happened to be about broken families.

“That sermon showed me that we’re not alone. We’re not the only ones with a family that’s not perfect,” Smallman said. “Meaning that there’s so much love and so much more than just having two happy parents, three kids and the dog. Like, it’s OK to be broken.”

From that moment on, Smallman wanted to pursue Jesus on a more personal level, shifting his perspective on Christianity from learning about a religion in church to forming a relationship with Christ. In fall 2020, Smallman became a Christian.

Smallman has loved music since he was young. His father was a professional drummer who had a wide collection of music, spanning from metal rock ‘n’ roll to jazz, Latin to pop. When Smallman began growing his faith, he was fascinated by the intersection of faith and music.

“Finding out through church that I can worship while listening to music I thought was the coolest thing ever,” Smallman said. “I guess meeting Jesus changed my listening.”

Nearly a year after becoming a Christian, Smallman submitted his FAFSA to only one school: Bethel. The night before move-in, he decided he would attend, packed up his entire room in four hours and moved into Edgren Hall. Smallman stayed involved in music, joining United Worship, a ministry at Bethel that forms worship music groups for Chapel and Vespers.

Now in his second year with United Worship, he serves as a team leader. Smallman feels his role in the group allows him a musical outlet and a venue to use his passion to worship the Lord.

“Worship was … the biggest thing that connected me with the Lord,” Smallman said. “Before I even went here, I went to Vespers, and I thought it was the coolest thing ever and it was one of the biggest reasons why I wanted to apply here.”

Now that Buckenmeyer, Carlson and Smallman attend Bethel and have explored and developed their faiths, none deny that God had a hand in their lives. Runion finds a biblical example for how to utilize Bethel’s diversity for each student’s benefit.

“My hope and prayer for our entire community is that we do this together,” Runion said. “Regardless of our backgrounds, our current … strength of faith or faith commitment, that we take a lesson from Jesus and live out our faith together.”

![Aaron Smallman plucks his bass guitar Nov. 10 at Bethel’s Friday chapel service. Smallman has been a United leader for the Vespers team for two years and appreciates the way worship and music intersect. “I [used to] listen to explicit, harsh, very earthly stuff that would bring me down and physically change my demeanor,” Smallman said. “I thought [it] was mind-blowing, to be able to listen to music and appoint it towards the Lord.”](https://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-20-at-9.42.30-PM-1200x798.png)