When Hawah Koroma’s uncle called her into the kitchen and said, “Hawah, I need to talk to you,” she figured she was in trouble.

He never talked to her like that unless she was being disciplined, but she couldn’t think of anything she had done wrong. But Koroma wasn’t in trouble. In fact, she found out that she and her sister would be moving from her home in Ghana back to where she was born – the United States. It was 2017, and Koroma was living with her uncle, younger sister and grandma.

The next morning, Koroma woke up thinking she was going uptown with some friends. Instead, she was met with a packed suitcase – the same suitcase she had come to Ghana with – filled with new blue jeans and striped shirts, as opposed to her normal private school uniform. She had no choice as to what she would take back with her. Only allowed to take one book with her, Koroma chose her Bible, leaving her blue diary behind.

There was no time for goodbyes or to process what was happening. She couldn’t say anything to her friends, neighbors or other family members. Nobody knew she was leaving Ghana for good, and less than 12 hours prior, neither did she. Koroma gave her grandma a hug and a kiss for the last time, not knowing that she would be unable to attend her grandma’s funeral when she passed away in 2022.

When they arrived at the airport, Koroma could see tears well up in her uncle’s eyes, only the second time she had ever seen him cry.

“It all got real when my uncle turned his back and I never saw his face again,” Koroma said.

Hours later, Koroma landed in Minnesota. After her Maple Grove classmates told her not to trust white people, a notion that opposed the one taught to her in Ghana, she took on the mission of understanding race issues in the U.S. herself. Six years later, Koroma leans on her education, friends who love the Lord and a mentor who has helped her discover her leadership skills as a Black woman.

—

Koroma and her younger sister Mugeegbaykola were born in Georgia, where their mom lived as a single mother after moving to the U.S. from Ghana in 1997. When Koroma was 4 and her sister 1, their mother sent them back to Ghana, where their uncle and grandma would take care of them for the next 14 years. She was struggling to provide for the two of them on her own.

Koroma’s uncle and grandma were her family. Kind of.

“Even though my uncle was there for me, I knew he wasn’t my parent,” Koroma said.

She remembers when she got her first period. She could see the panic in her uncle’s eyes. He fumbled around, procuring a pad and a pair of underwear. He flipped the pad upside down, wrestling with the task. Eventually, he turned to his girlfriend for help. This was the same uncle who had bought her first pair of heels, coached her on shedding her tomboy image and delved into the mysteries of the male mind.

But in 2017, the girls found themselves back in the United States, this time in Minnesota, where Koroma would attend Maple Grove High School her junior and senior years. Going from a student body of nine to 2,000 was not the only shock to her system.

“I’ve never seen that many white people in my life,” Koroma said.

Her eyes scanned the locker common area. The left side was all white people, and the right side was all people of color.

Why? she thought to herself.

Koroma’s high school experience was marked by distrust and warnings about racist sentiments.

“Don’t mess with white people, because they’re racist,” she was told. She went on with this narrative, assuming her peers didn’t like her because of the way she looked. White friends remained elusive during those years.

Racism was not a word in Koroma’s vocabulary when she came to the United States in 2017. Despite being familiar with slavery, her British curriculum in high school wasn’t focused on covering things like the transatlantic slave trade.

Instead, watching Meghan and Prince Harry get married was a monumental moment.

To Koroma, the United States was a contentious mosaic of diversity, unlike Ghana where differences stood out but were ultimately embraced. In Ghana, she experienced a warm community where people strived to integrate, understand and treat one another like royalty. However, upon arriving in the U.S., Black American students taught her about the need to pick sides, cautioning against trusting white peers due to systemic racism. She found herself questioning why the reciprocity she witnessed in Ghana didn’t extend to her.

Why don’t white people look at me the way we look at them when they come to our country?

The divide was palpable, and she wanted to know why.

“Here in America, it’s largely different because I’m a certain color,” she said.

Koroma acknowledges the hurtful history of Black Americans and is reminded of it when breaking news hits the headlines. Like the killing of George Floyd, and Daunte Wright, who was killed just ten minutes from Koroma’s mom’s front steps.

“Yes, the odds will always be against me because of my skin color,” she said. “But does that mean I don’t belong in a place as equally as they do? No.”

Replacing the term “racist” with “ignorant,” she recounted encounters of cultural naivety, like a young girl asking if there were gorillas in their African backyard.

“I wouldn’t call that racist. She’s 5,” she said.

Mugeegbaykola had her own struggles with the transition from Ghana to the U.S., noticing the fast-paced environment and many cultural differences. She has been able to look to Koroma as a role model.

“She was really helpful because we were both going through similar emotions,” Mugeegbaykola said. “So we understood each other and she was my main support system because she understood certain things way better than I did.”

Koroma emphasizes the impact of upbringing and environment. Her mom put CNN on every morning so that they could have informed conversations about what was going on in the world. That’s why she feels like education is so important. Koroma has confidence in her ability to talk to anyone without feeling scared or timid, even when delving into big issues like racism.

“I know I’m educated. I know [that] I know what I need to know and when it comes to times I need to defend myself as a Black young woman, then I will do that,” Koroma said. “But to sit back and not work hard because of things that happened in the past — I can’t do that.”

At Bethel, she has learned to reject the notion that every white person is racist.

“I look at the way you treat me, and I go off that,” Koroma said.

Koroma finds investing in and learning about other cultures is the most practical way to break the barriers that racism has built. Koroma can speak five languages and also attends a Spanish-speaking church. Education became her armor, a means to combat preconceptions.

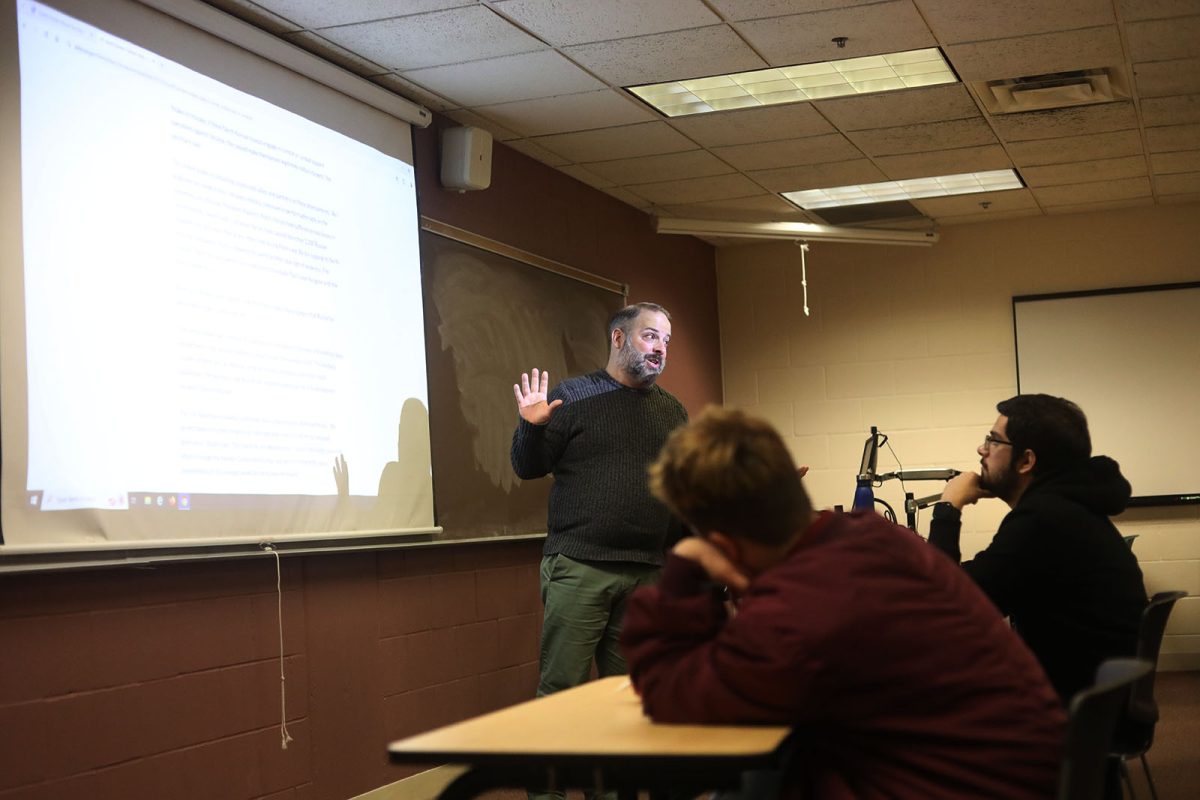

“I think the hard part of Bethel is it’s a culture shock for a lot of people of color, and for a lot of our white students,” Dean of Inclusive Excellence Jamey Johnson said. “We have a lot of white students who have never been around people of color, who’ve been in their own mono-cultural environments.”

Johnson has served as a mentor to Koroma since she arrived at Bethel, discussing everything from friendships to Koroma’s vocational calling. Along the way, Johnson has witnessed growth in several areas in Koroma, including her intentionality in leadership, personal development and self-love.

“She’s got a resilient spirit and that’s an honor for me as a mentor, pastor and a friend,” Johnson said.

Not wanting Koroma and her sister to not get too comfortable, their mother advised them to talk to anyone, no matter the color of their skin, preparing them for diversity in the workforce. And if she were ever doubted because of her name, because she was a woman or because she was Black, her mom told her to “put pen to paper.”