After a stormy childhood, Will Kah uses music, love to navigate the racial landscape at Bethel.

Abby Petersen

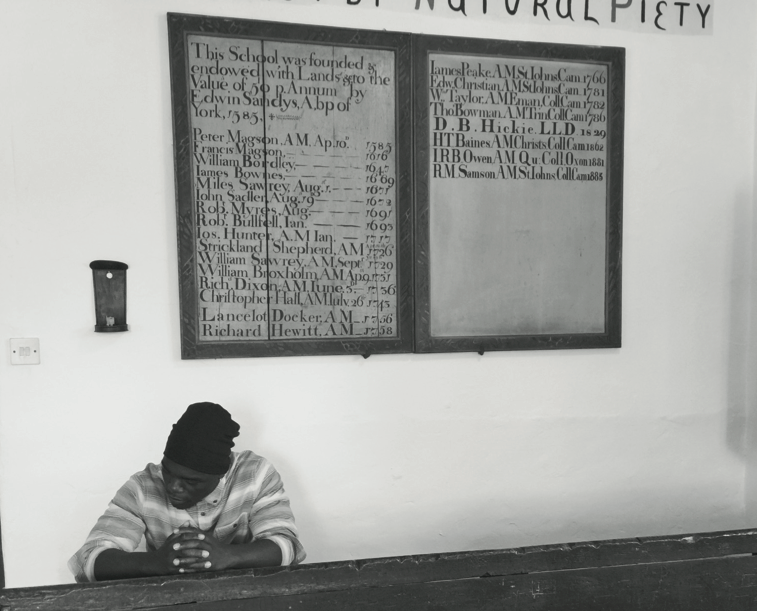

Will Kah’s mind goes numb as everyone looks at him and waits for him to answer the question about race. He’s 21 years old at Bethel University and he’s the only black student in class.

Things were different 15 years ago. Will was six-years-old and shivering on the floor of a house in North Minneapolis, fighting 10 other people for a spot by the lone heater. It had been two months since there was food in the fridge. When he’d go outside, he would see cops pulling guns out of the trash, people getting arrested and people getting hauled into ambulances. A young girl’s uncle was murdered. Someone bombed his friend’s house. It’s either fight or get beat up in the ghetto. But in the ghetto, it didn’t matter that the color of his skin is black.

It mattered in the suburbs that Will moved into when he was 11. Immediately, Will didn’t feel like he fit in. He tried out for the football team.

He had his Uncle Martor, his father-figure who taught him how to ride a bike, how to talk to girls.

“Be careful who you eat with,” Uncle Martor would say.

Will knew what he meant. “Be careful who’s around you and who you let get close to you.”

When Martor went to jail and things began to change. Kah felt his heart harden. He was bigger than the other kids so he started bullying them, treating seventh grade like a street fight he used to have back in the ghetto.

High school hit him like a concrete sidewalk. Kah’s mom married some guy from Africa. His eighth grade teacher, the only one who ever seemed to care, died.

One day Will’s friend suggested that he come along to a Christian group called Student Venture. Kah didn’t like the sound of “Christian”, but there was pizza so he obliged.

“What does it matter if you love God,” Kah thought from the back of the room at Student Venture. Kah loved his uncle and he got deported to Liberia. But the idea of Christ bounced in the back of Kah’s head like a drumbeat.

Soon Kah was a junior in high school and hitching rides to church every week. He was the captain of the football team and recording hip-hop music. Rhythms and rhymes filled Kah’s brain. He cruised through the year until his mom left.

Homeless.

Kah bounced around before the places to stay started to run out like a fading verse. He curled up each night on the floor of his uncle’s old house. A little blonde lady named Tami Moberg showed up to one of Kah’s football games. She wanted to know where he was living.

“If you ever need a room, we have one,” Tami said to Kah. Homeless, no more. In the fall of 2013, at his new family’s prompting, Kah started his freshman year at Bethel. Just as the lines of his life had come together, everything fell apart.

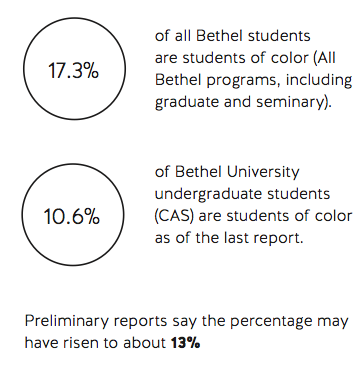

He’s the only black kid in class and all eyes are turned toward him. “There was diversity in high school but there isn’t here,” he said. According to Kah, the football coach sweeps racism under the rug. I follow Jesus Christ and so do these people, Kah thought at first.

“I call black people who are criminals and stuff ‘niggers’ but you’re regular,” a kid in the hallway said to Kah.

“What the hell do you consider being black?” Kah fumed inwardly. “Shit,” he thought, contemplating transferring.

Nobody seemed to want to talk about race. Tim Hunt, a black senior at Bethel and Kah’s best friend thinks so too. “Race to Bethel is like religion to America,” Hunt said.

“They’re opting to have the comfortable conversations.” Everyone seems to have questions, Kah thinks, but they are questions people are afraid to ask. During his freshman year, on the verge of transferring, his grandma, uncle, and his eighth-grade teacher, cared enough to teach him to succeed. The Mobergs bringing him in. The hip-hop. Jesus broke through barriers and that’s what Kah wants his music to do.

“If I can’t love anybody else, nobody’s gonna love me,” Kah said. “What happens if we get to heaven and I’m still black and you’re still white?”

“So many of my students don’t want to talk about [race],” Becknell said. “That’s Will, in my mind: unafraid to ask the big, bold, provocative questions.”

Now a junior, Kah is traveling the British Isles on England Term. His name brings a smile to faces like that of Bethel professor Thomas Becknell.

Kah is thankful for the progress Bethel has made in talking about race, including the Black Lives Matter forum last year and the United Cultures of Bethel groups set up to bring support to people of different races. For Kah, it all comes back to love.

“Love means getting outside of yourself. Being willing to talk to the woman at the well. Being willing to be in the same room as a prostitute like Rahab. Being willing to touch the leper.” Will reminds the Bethel community. “If we can’t do that, then Christ must not be real.”

![Nelson Hall Resident Director Kendall Engelke Davis looks over to see what Resident Assistant Chloe Smith paints. For her weekly 8 p.m. staff development meeting in Nelson Shack April 16, Engelke Davis held a watercolor event to relieve stress. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to really invest and be in [RAs’] lives,” Engelke Davis said, “which I consider such a privilege.”](https://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/041624_KendallEngelkeDavis_Holland_05-1200x800.jpg)