“ ‘Being Gay’ opened discussion but failed to establish claims, overlooked ‘Christ & Culture’ Issues.”

Dr. Daniel Ritchie | English Professor

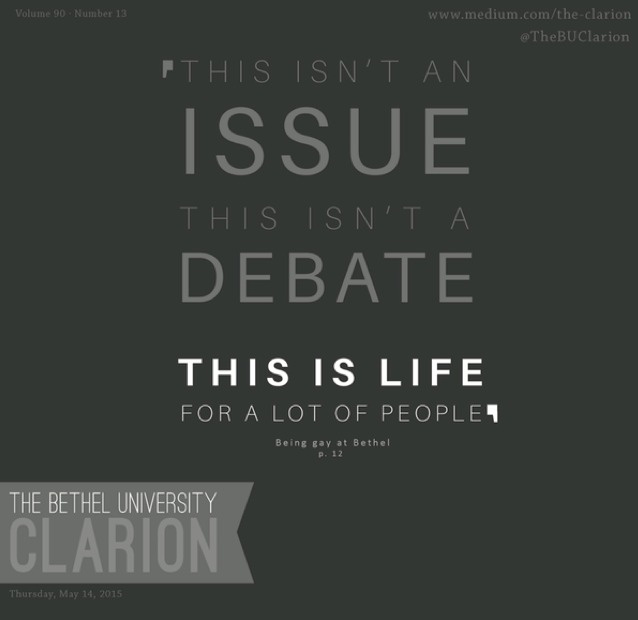

On August 24, English Professor Dr. Daniel Ritchie wrote a letter to the editor in response to the article titled “Being Gay at Bethel” printed in the Clarion last May. Dr. Ritchie’s letter is as follows.

To the editor:

In the article, “Being Gay At Bethel,” printed in the final issue of the Clarion last spring, the writers correctly pointed out Bethel has been reluctant to engage LGBT issues on an institutional level. The writers overlooked campus talks in recent years by Mark Yarhouse, Lisa McMinn and others, but President Barnes admitted in a chapel talk last fall that we have done little to address the questions surrounding marriage — of which LGBT issues are a prominent part. It’s a strange situation, given our claim to “engage the most important issues in our culture,” as President Barnes stated in the Summer 2015 Bethel Magazine.

While I appreciate the Clarion’s willingness to write about the issue, however, the article has many shortcomings. Since there was no opportunity to respond at the time, I offer this response now.

First the article does not establish the accuracy of the major claim that the authors make in their own voice: that “at Bethel University…being gay is a reportable offense.” This claim is fundamental to the article’s assumptions and to the issues it chooses to pursue or ignore.

The authors make this claim in a paragraph that uses – or misuses – a Student Life handbook for student Resident Assistants. Because student RAs are not adequately trained to deal with a host of issues on their own (Acting Dean of Student Life, Marie Wisner later explained to the faculty)— issues such as cutting, past abuse, homosexuality, etc.—they must refer them to professional Resident Directors, who have received such training. It is not accurate to infer that this makes homosexuality (or the other issues on that list) an “offense,” reportable or otherwise.

We can analyze terms like “report,” “refer,” “tell,” or “inform” forever. But this avoids the question. The question is whether “being gay is a reportable offense” as the article claims. If it is not an “offense” it cannot be a “reportable offense.” The article relied on Student Life documents, but it offered no evidence that those documents show that being gay at Bethel is an “offense.”

I know it is common to defend articles that fail to establish the facts surrounding their major claims. Even if the facts are lacking, these defenses usually go, they tell an essential truth nonetheless. In this case, however, such a defense is unbelievable due to two other journalistic failures:

1. What explanation could the Clarion writers have given for failing to ask Dean Wisner to confirm, disconfirm, or at least comment on their claim that “being gay [at Bethel] is a reportable offense”?

2. Moving from documents to practice, if being gay at Bethel is an offense, the three profiled students should have undergone disciplinary procedures through Student Life. What explanation could the writers have given for failing to report on the presence or absence of such disciplinary procedures? Or for failing to consider what the presence or absence of such procedures signifies for their article?

The strength of the article has been to help us listen to the stories of three gay students and sympathetic former professors. That’s an important contribution. But journalists must do more than provide a platform for the people and causes they sympathize with. They must probe deeply enough to place the story in their readers’ full context.

This leads to a second major shortcoming in the article.

The Clarion article gave some historical background for this issue at Bethel, stretching back to 1991. But it neglected to note the role of evangelical women, including Bethel’s Alvera Mickelson, in resisting the gay drift of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus just a few years before. In the late ‘80s, Alvera and others formed “Christians for Biblical Equality,” whose very name indicates that not all culturally acceptable forms of equality are consistent with Christian discipleship.

Equality, in a virtually unqualified form, is the dominating political element in progressive culture today. And this element has been a primary basis for the cultural acceptance of homosexuality and marriage equality. The article often seems to assume an equality of gay relationships to relationships between a man and a woman. For instance, Dan Sandberg comments that “it’s not about who you love, it’s about how you love.” By failing to probe beneath such statements, the Clarion article uncritically reflects those cultural assumptions as well.

Every student in CWC and Humanities should think more deeply about the relationship of Christ and culture than this. As written, the article uncritically mirrors progressivism’s embrace of equality. And when Christians mirror their culture, writes H. Richard Niebuhr, they follow the “Christ of Culture” (misleadingly labeled “Christians affirming/absorbing culture” by our two courses). For such Christians, Jesus is the hero of culture. He embodies its finest value, however partial and insufficiently biblical it proves to be, whether that value is success, patriotism, consumerism, enlightenment, or equality. To follow him is to spread that value and attack its enemies. For progressives, social justice is thus identified almost exclusively with equality. And ironically, many formerly radical Christians, who preached a counter-cultural faith 40 years ago, now often provide little more than a pious echo of New York Times editorial positions.

Similar uncritical assumptions surface in the article’s quotes from Curtiss DeYoung, who equated affirming LGBT relationships with catching up to changing perspectives and “choos[ing] grace.” If this is not a progressive version of the “Christ of Culture” – that Jesus suffered torture and death so that we would have the grace to accept gay sex – what would be?

A Clarion editor should be more alert to the way today’s events reveal these issues—and should reflect upon them more critically. For by promoting equality to the neglect of other elements of social justice (liberty, sanctity, authority, the rule of law, etc.), we compromise the witness of Christ in our world. This is dangerous. Over the last year it has led progressives to downplay and even ridicule the ever-increasing threats to the free exercise of religion. Now, denying people their civil rights is normally viewed as unjust. But if discipleship is following the Christ of progressive culture, apparently, we will ignore the intolerance of accreditation boards when they bully a sister college (Gordon); we will turn aside when state judges fine Christian bakers or photographers for exercising their religion by refusing to participate in a gay wedding ceremony.

I think we uphold biblical sexuality at Bethel because it’s a good thing. When Jesus describes marriage between one man and one woman in Matthew 19, he twice indicates that it was God’s plan “in the beginning” at creation. Unlike today’s socially constructed views of sexuality, the doctrine of creation takes seriously the givenness of our embodied nature. We receive the differences between male and female as gifts, not as occasions for Gnostic speculations about gender. And rather than accepting our culture’s degradation of marriage to a sexualized friendship among individuals, we celebrate it as God’s way of bridging and preserving the mysterious diversity of creation. Our cultural conversation about sex now focuses almost exclusively on the equality of rights among adults – a sure guarantee that (whatever our rhetoric) our actual social practices will promote individualism. Biblical sexuality, by contrast, acknowledges the relation between sexuality and the nurture of children. And all of these children, by the way, should have an equal right to a moral, social, emotional, and legal relationship with a father and a mother – an equality that is currently denied the 40% of American babies who are born out of wedlock and into a life that is over five times more likely to start in poverty. This is social injustice on a massive scale. Our culture’s confusions on sexuality (of which the LGBT issues are only a part) are making it worse.

We can speak into these issues with clarity and compassion, if we will. It is my hope that this year’s Clarion staff will address them with a deeper awareness of the Christ and culture issues they bring up. Presenting them in a way that develops our community’s dialogue is a difficult task. I wish you well.