Recent University of Minnesota graduate Soren Stevenson loses an eye to a rubber bullet during a protest in Minneapolis.

By Molly Korzenowski

Soren Stevenson, 25, looked to his left, watching a flash grenade explode in front of him. Another exploded to his right and he heard a third go off behind him. A fourth grenade crossed his vision. Stevenson turned to look, only to be hit directly in his left eye with a rubber bullet.

It had been five days since the death of George Floyd, the first Sunday of protests in the Twin Cities. Stevenson and a group of friends, including his girlfriend Liz Heehn, had been protesting in various marches around the city every day since they began.

“We’re supposed to seek justice, love mercy and walk humbly with God,” Stevenson said, referencing Micah 6:8. “I don’t see this [movement] as being any different than feeding the hungry and giving to the thirsty.”

A sheet hangs from the window of his walk-out porch reading: “Minneapolis demands justice.” A group of potted plants crowd the window as Stevensen takes a seat on a squishy couch, his left eye sealed shut. He lost his eye more than two weeks ago during the protest on University and Interstate 35W in Minneapolis May 31.

“The first protests were pretty gnarly,” Heehn said. “By Sunday, I felt like we had a handle on it, we knew what we were getting into. I think that’s what was most surprising, not that something happened, but that it happened when it did.”

Stevenson graduated this spring with a master’s degree in development practice from the University of Minnesota. Before that, he got his bachelor’s degree in human biology from Seattle Pacific University in Washington. Stevenson moved into a white house in Minneapolis a few weeks ago, with his college friends and a blue-eyed tabby cat.

Dave Muhovich, a nursing professor at Bethel, has walked through those wooden doors many times during the weeks following the incident. Muhovich met Stevenson’s parents as they served together as full-time missionaries to Uganda for 6 years and he has been a close family friend ever since.

“It seems to me that Soren is willing to put in the effort to make this terrible thing be used for good,” Muhovich said.

The day of the incident, Stevenson and his friends gathered together to protest outside of Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s home at noon in Southwest Minneapolis to call for the arrest of the three other officers involved in the death of George Floyd.

After a break for lunch at the restaurant French Meadow on Nicolette, the group went to the march at University and I-35W, where a tanker truck had driven through protestors only about an hour before.

“By the time we showed up, what I noticed was it was peaceful,” Stevenson said. “There weren’t bottles dropped, rocks, anything from the protestors, nothing being thrown.”

The sidewalks and streets were crowded with people as an organizer led chants and spoke to the crowd from the front. Stevenson and Heehn separated from their friends and moved forward in the crowd. Stevenson stood a few rows ahead of Heehn, standing on the far left side of the crowd. He linked arms with the protester to his right.

“The call that brought him to the front was ‘White bodies to the front,’ the idea of white people linking arms in front of protestors is supposed to be a de-escalation tactic,” Heehn said. “While this was a de-escalation tactic, it clearly did not work.”

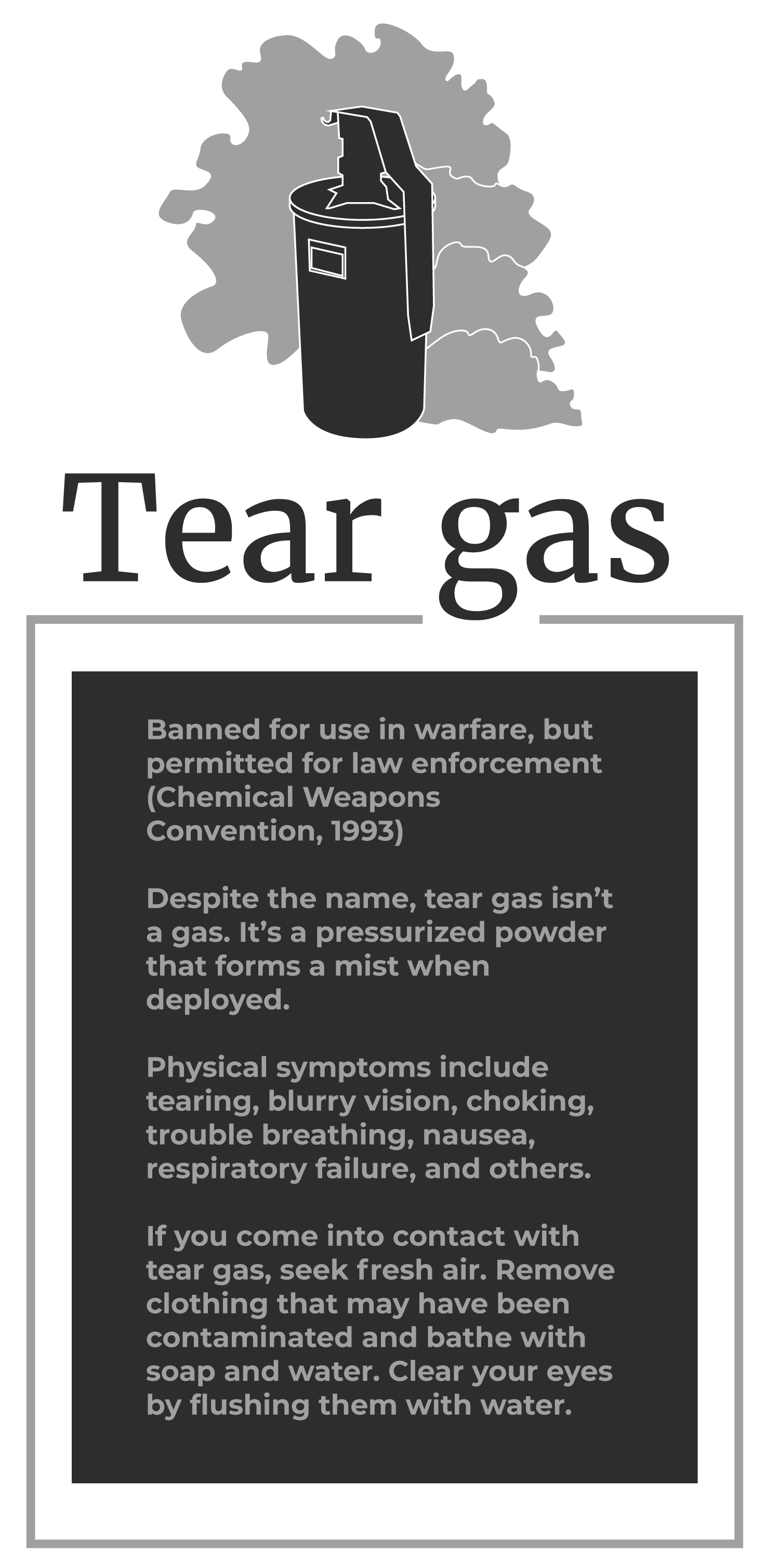

At that moment, about 6:50 p.m., Heehn and Sorenson said police began using force, throwing flash grenades, shooting rubber bullets and showering the crowd in tear gas. Heehn recalled a woman keeling over in pain as the gas entered her system. Protestors poured milk and water on her to alleviate the burn of the gas. Heehn watched as chaos erupted, people running every which way. But she said the front rows stood strong.

Heehn said police presence had been growing, and tensions may have been higher after the tanker truck blew through. However, both recalled only hearing peaceful chants, such as: “Hands up, don’t shoot” and “Say his name: George Floyd.”

Neither Stevenson nor Heehn heard any verbal warnings from the police.

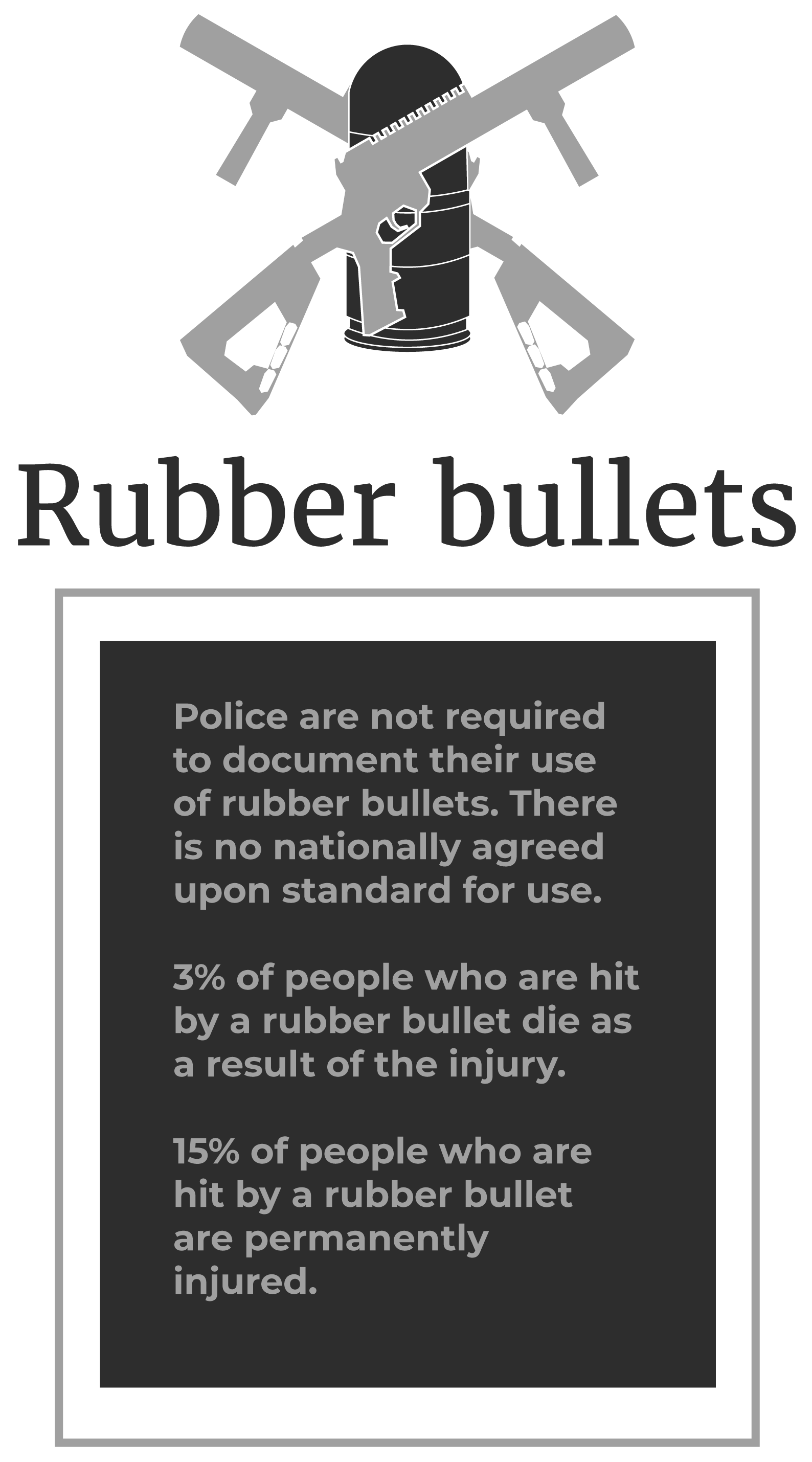

Stevenson, standing among those in the front row, was hit directly in the left eye by a rubber bullet. According to a 2017 study by the British Medical Journal, such bullets travel at similar speed to lethal bullets and can cause death or severe damage when shot at vital organs, like the head, neck, chest and abdomen, at too close range.

He keeled over and felt his face; everything was soft and he couldn’t see out of his left eye. Stevenson remembered reading about a reporter who had lost an eye from a rubber bullet and realized that’s what had happened to him. According to the Pioneer Press, freelance journalist Linda Tirado was blinded in one eye by a less-legal projectile in Minneapolis only a day before, one of many others injured during the protests.

Stevenson took off to the back of the crowd, where he was discovered by a group of U of M nursing students in medical scrubs. They poured water over his face and covered it with a bandage.

The volunteer student medics got Stevenson into a car and took him to the nearby M Health Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center. There, Stevenson underwent surgery to try to repair his damaged eye. He stayed in the hospital for 24 hours before being released to recover at home.

Heehn said Stevenson was still in severe condition that first week. He would throw up and pass in and out of consciousness while on heavy pain medication. He suffered from a concussion, a broken forehead, nose and eye socket, along with hairline fractures throughout the left side of his face caused by the impact of the bullet. He will endure more surgeries in the next eight to 10 months to correct these.

During that first week of recovery, Stevenson’s parents and friends came to visit. Muhovich got a phone call from Stevenson’s mom shortly after he was released from the hospital, asking him for help with Stevenson’s at-home treatment protocol. Muhovich came in to check on him every few days during his recovery.

“I was skeptical that a rubber bullet could do this much damage,” Muhovich said. “It’s a high-powered projectile. I would be in favor of their out-right banning or extreme use only.”

On June 10, Stevenson went into surgery a second time to fully remove his eye, which was deemed unsalvageable. The eye was then replaced with a prosthetic designed to attach to muscle tissue and move around like a real eye. He will go in for yet another surgery in a month to prepare him for a glass eye, a lens that will make the prosthetic appear eye-like.

“I’m proud of him, I think of him as a hero,” Muhovich said. “Partly because of what he did [at the protest], but I’ve been mostly proud of him because he hasn’t slipped into self pity; his individual case is just indicative of the broader, important issues.”

Stevenson retained a lawyer shortly after the incident as well. According to Muhovich, he plans to seek charges against the MPD officer who shot him. Keehn said Stevenson’s lawyer has not yet filed a use of force report with MPD. The Clarion asked for police comment, but they were unable to do so without the report.

Medical bills have been estimated to total at $300,000. A GoFundMe has been started for Stevenson to help him raise money for his procedures.

“As much as this is about Soren, gosh, my heart breaks for this poor, snarky boy losing his eye and being in pain,” Heehn said with a smile. “I hurt for his hurt. But, it’s not about him – it’s about everything that we’re working towards, it’s about this whole broader movement happening.”

Stevenson looked out the upstairs window at a flat spot on the roof where he and Heehn would lay out under the spring sky, enjoying the big blooming tree that hid them from neighbors. He said he was happy to be moving around again, feeling well and “not throwing up anymore.”

“I’d like to keep my other eye,” Stevenson said, chuckling. “But this can’t knock me out… because the movement can’t stop.”