By Sierra Beilby

When I student taught at Minnetonka High School, I recognized myself in my 10th graders. I pretended like I didn’t; I had to reinforce that my new red oxford shoes made me an adult who knew nothing about TikTok. I remember calling a student to my desk to talk about his lackluster Great Gatsby essay. He leaned over me and crossed his arms. I swallowed the lump in my throat, which told me he has more power than me, and asked him what he liked about his project.

“Nothing,” he said shortly.

“Nothing?” I asked, “Don’t you think the themes in the Great Gatsby are interesting?” I hoped something in the green light would give him a personal revelation so I wouldn’t have to use my squeaky teacher voice.

This student looked me in the eyes and said, “I don’t care about learning this. All I care about is an A in the gradebook.” My face flushed with hypocrisy to think that I said the exact same line to my 12th grade english teacher and my D-Tag professor.

I’ve done my time feeling stupid because I can’t pass AP exams while my friends rack up college credit. I’ve also done my time feeling like the smartest kid in the room, and had no fear to raise my hand and talk about critical lenses in Marxism. Now I’m going to be a teacher, where I will always be the smartest kid in the room. What do I do with this, knowing that in some ways, my students are past versions of me?

Sometimes I hear people say the education system is broken. As a future educator, I think about what the purpose of school actually is, and reimagine the ways that external rewards are assigned.

I never had math with my friends in high school, they were all in advanced math. I was in dumb math. Nobody called them honors geometry and geometry. The hallway language was smart math and dumb math. And as a dumb math kid, I felt the apathy of the room. I didn’t listen to lectures. I doodled trees, flowers and cursive song lyrics when I should be taking notes. I felt lost doing homework and exams; the test scores perpetuated what I already thought was true, that I was ignorant. I supposed I could have “tried harder.” But when you’re in dumb math, you know you’ll never make it to smart math. It’s like the 10th grade soccer coach saying you “might get JV playing time.” There is no mobility in this educational hierarchy.

I sat angrily at my desk, because someone somewhere decided when I was a 5th grader that I couldn’t do advanced math. What was wrong with me?

I remember my dad and I chatting one day over heavy metal on the car radio. He told me school is less about appearances or efforts, and more about “playing the game.” If I could learn the game’s rules, I could win.

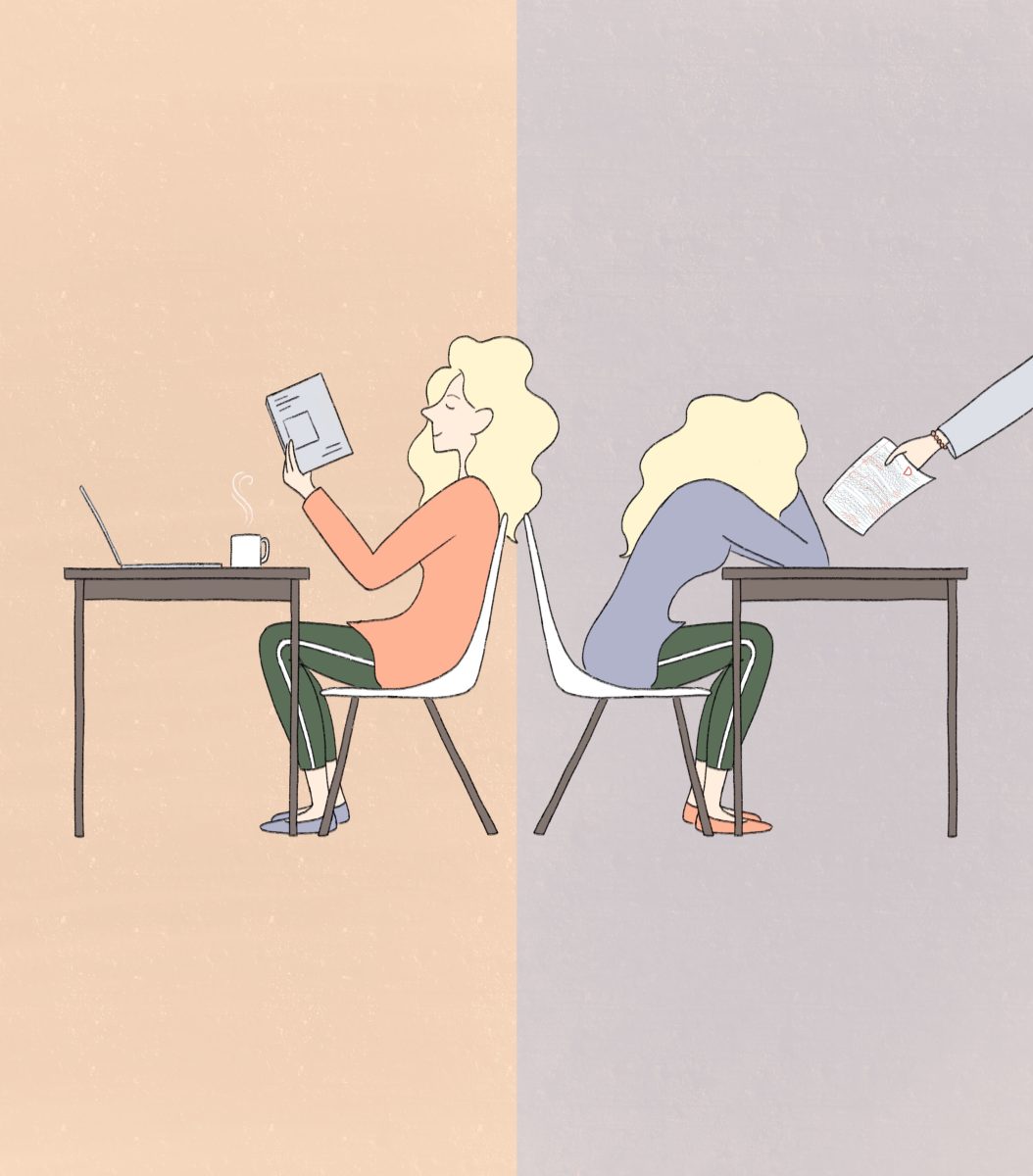

A prevalent narrative in education assumes earning an A has more to do with intelligence than learning. A doesn’t necessarily mean you’re smart, A means you tried. Which is sometimes true, but not universal. Yet society perpetuates this system. If schools get more students to take AP tests, they get more funding. Students are pushed into honors tracks, enamored by the potential of graduating with honors. External reward systems tell students it doesn’t matter what they think about, only what they produce. This is academic capitalism. It’s the little league dad on our shoulder, telling us participation trophies are for losers. Success is a first place trophy or bust. An A or bust.

I bought into the game. At Bethel, I told myself I was going to get A’s. I swore to myself I would grab school by the collar and be intelligent. But what did my grades really prove? I knew the right things to raise my hand for. I figured out which texts were worth not reading. I checked my grades religiously, preemptively writing strongly worded course evals in my brain if I didn’t get the magic letter on my transcript. I was every kid I envied and resented in smart math. This was the game.

Here’s my challenge, Bethel—let’s not let external rewards or academic capitalism determine how we think about ourselves. The most critical thinkers in class could be getting Cs. They could be the student sitting next to you who thinks they are dumb. Not every A student has put in A effort. We all have a relationship with education that looks a little like “it’s complicated.”

Is the education system broken? Not in whole. But it’s time to stop judging our intelligence by a traditional grading system, and start looking for creativity, activism, originality and critical thought.