Biblical and theological studies professor Juan Hernandez describes his experience at a protest this summer.

Callie Schmidt | News Reporter

Associate Dean of Off-Campus Programs Vincent Peters stepped up to the microphone in Benson Great Hall the morning of Aug. 29.

“Go away,” Peters said.

The crowd went silent.

“Just go away. Get lost! Just get lost. Go away, come back as a kinder, gentler, better, wiser, and a holier person. Go away to build up a people and culture so different from you. You’ll find it’s a small world after all,” Peters said.

“Go away to learn, speak, and understand a different language. Get lost! Allow yourself to get lost in the world. What better way is there to learn about yourself? The world needs you for a better future for all.”

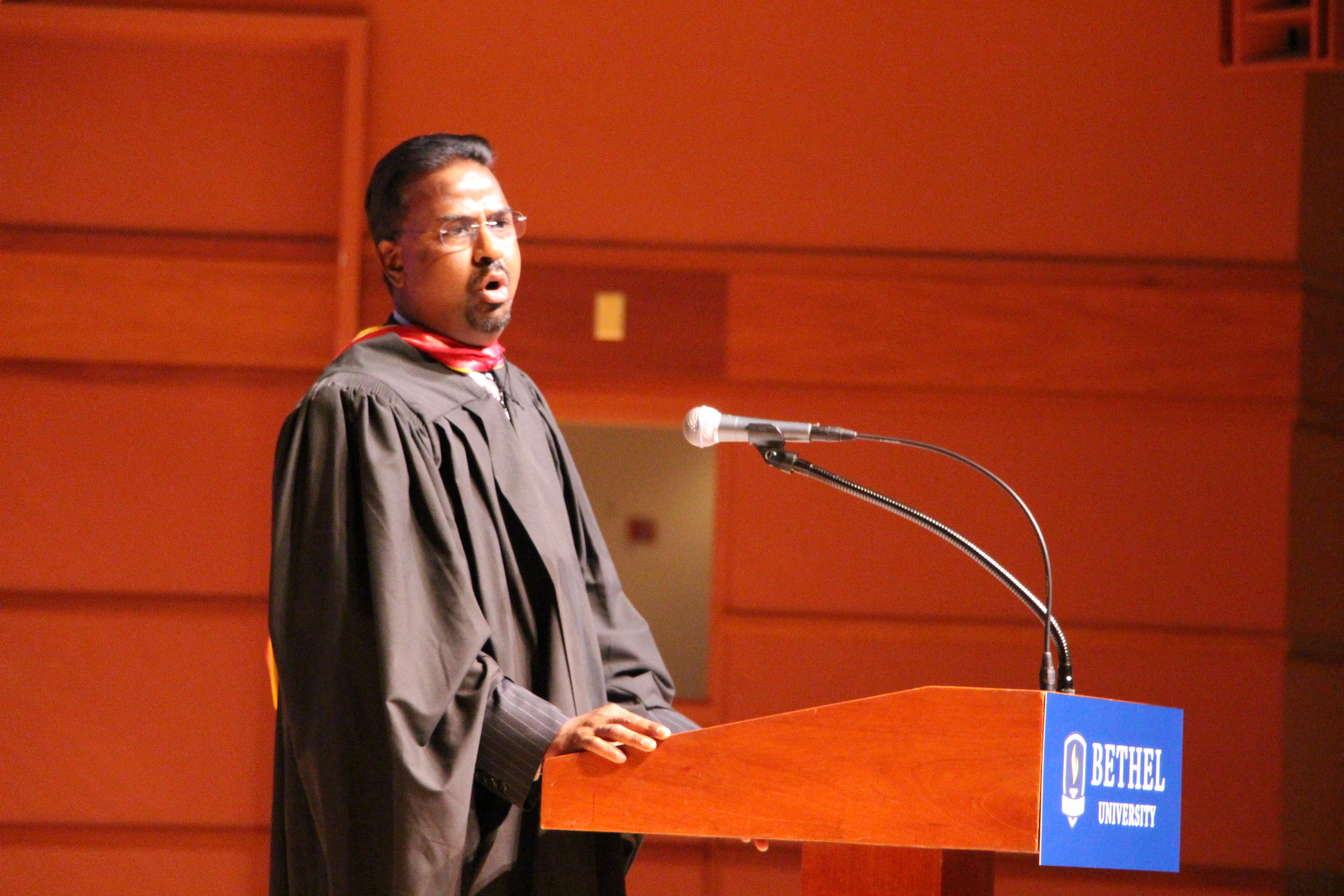

Peters sat down. Biblical studies professor Juan Hernandez Jr. walked up to the podium.

Hernandez never went to protests. He avoided crowds. This changed the morning of July 8, 2016.

Hernandez was flipping through the news when out of the corner of his eye, he saw the video footage of Philando Castile, an African American male who was shot four times by police officer Jeronimo Yanez. Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, live-streamed the aftermath on Facebook. Her daughter was in the backseat.

The shooting took place in Falcon Heights, Minnesota.

“Within a mile of where we worship today and on the road to my daughter’s camp. The proximity felt like an indictment,” Hernandez said.

According to Hernandez, it wasn’t long before he found himself driving down Larpenteur Avenue, the same road on which Castile had lost his life approximately twelve hours prior. A group was gathering to protest at Governor Dayton’s residence.

“I felt compelled to be there. I didn’t have a plan, and I hadn’t really thought through what I was doing. There was no strategy. And I certainly wasn’t worried about effectiveness. The only thing I knew was that I could not get there fast enough. My heart raced, and I was nauseous. I had to be there, if only to weep with those who weep,” said Hernandez.

Hernandez left the protest. He picked up his daughter from her last day of camp, where there was an ice cream social for the kids. He had to travel back down Larpenteur to get there, yards away from the traffic stop that turned deadly for Castile. He felt sick to his stomach.

Hernandez took his daughter to the corner of Castile’s traffic stop, hoping to show her that what had happened to Castile wasn’t just someone else’s problem.

“That racial and ethnic biases appear to play a role in Minnesota traffic stops is just one of the many disparities that afflict the state,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez reminded the Bethel crowd who Christ came for in the first place – the poor, the captives, the blind and the oppressed. According to Hernandez, it would take no great leap of the imagination to recast these categories and apply it to people today in terms of disparities – the overlooked, the discriminated and the victimized.

“We here at Bethel are not at liberty to distance ourselves from recent events,” Hernandez said. “This is a call to action.”