How LaTroy Hawkins, a retired MLB pitcher and current Minnesota Twins assistant manager, climbed his way out of poverty and helps those who weren’t fortunate enough to do the same.

By Maddie DeBilzan

LaTroy Hawkins was a black man at Westside High School in Gary, Indiana — where over half the population was “economically disadvantaged,” where drugs came through like a monsoon and flipped the city upside down, where the primary income came from declining U.S. steel mills, where the only way to escape from the oscillating cycle of teen pregnancy and empty beer bottles and shattered windows and shotgun thunder was to either be really, really good at sports or smart enough to stay in school.

Neither were very likely. But LaTroy was on his way to getting drafted the winter of his senior year. He was the exception.

Which is why his high school basketball coach, Joe McClain, took a paddle to his behind in the Westside locker room during halftime. Because despite the team’s 18-point lead, if Hawkins had tried harder, they’d be up by 20.

When Mcclain met LaTroy, the kid was a hot head who couldn’t recognize his own talent. There was something different about LaTroy. So he smacked his behind right through that Gary, Indiana barricade.

But this isn’t a story about basketball.

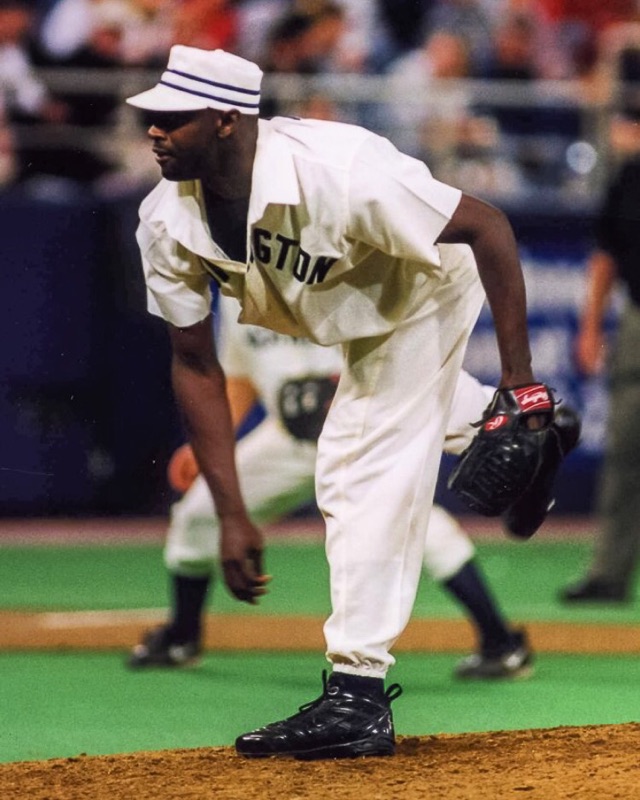

Hawkins was even better at baseball. The Minnesota Twins drafted Hawkins into the minor leagues right out of high school. When he turned 22, the Twins had a few empty slots on their roster, and Hawkins filled one of them. A magic arm, they told him. That’s what he had.

This isn’t a story about baseball, either.

He grew up with a single mom in Gary, which is a half hour past Chicago on Interstate 90. Dad never stuck around. LaTroy and his two brothers always had a ball in their hands. They’d go to the Tolleston baseball fields almost every day because they didn’t have anything else to play with except checkers and Connect Four. When LaTroy pitched, one of his brothers would catch, and vice versa.

One time, LaTroy and little brother Ophos were supposed to stay inside while their mom was cutting hair. But a few kids were outside talking trash into their window, so the Hawkins boys walked outside and beat them up. They got the belt for that one.

Some days there was snow on the ground, but no heat in his home. Didn’t seem to bother him too much, though. He had a grandfather who led him to Carter Memorial Church, a grandmother with a sweet smile that crinkled at the edges, a mother who worked to make sure he always ate dinner before bedtime.

He also had a bionic arm that would eventually clear the looming clouds of canned dinners and patched jeans and cold beds.

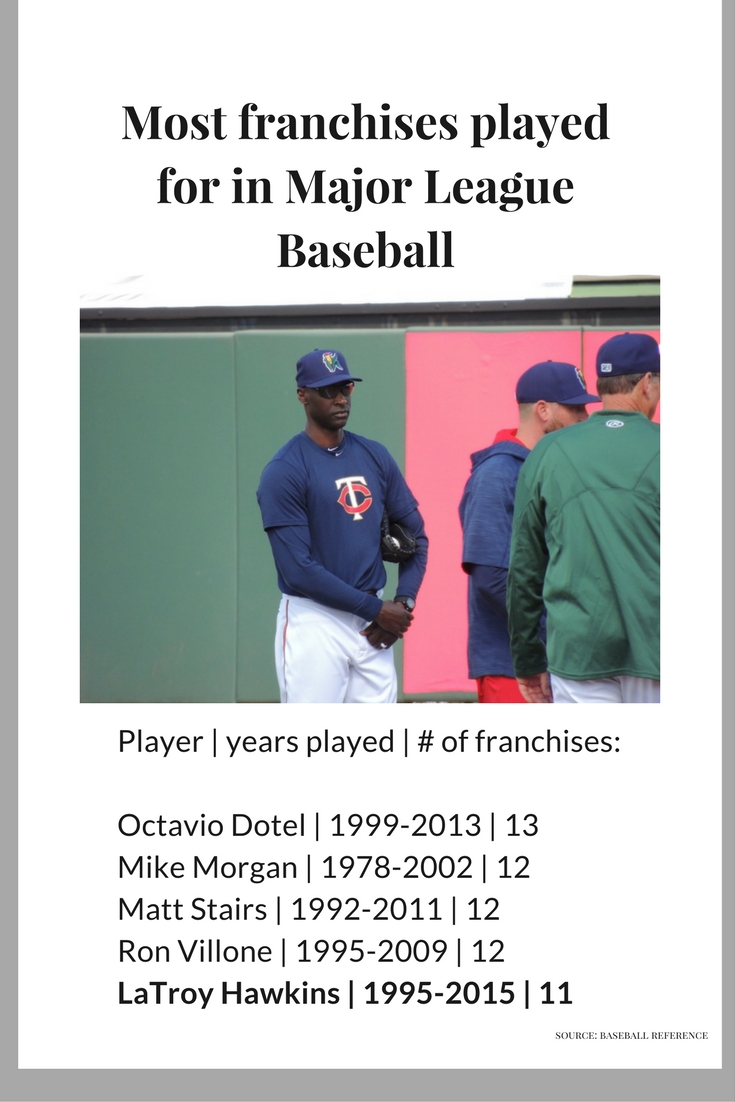

LaTroy Hawkins was drafted out of high school by the Gulf Coast League Twins, a minor-league rookie team, before being drafted by the Minnesota Twins in 1995, where he spent nine years. Hawkins pitched 1,042 games and and his career earnings are around $50 million, according to Baseball Reference. He retired in 2015 after spending 21 years in the big-leagues and pitching for 11 franchises.This fall, he was hired — along with Torii Hunter and Michael Cuddyer — as an assistant manager for the Twins to bring in a winning attitude. Hawkins lives in Frisco, a suburb in North Dallas, with his daughter and wife, and will travel to Minnesota three or four times this season.

MIRRORED BACKGROUNDS

Hawkins’ big brother Ronald Sewood was put in prison, accused at 22 for carjacking. According to a 2013 article written for the Star-Ledger in New York, police reports also say that Sewood, along with two other suspects, abducted a couple at gunpoint and took turns raping a 19-year-old woman. The man who accused Sewood of the crime was murdered during the investigation. Sewood, according to the article, has “proclaimed innocence since the moment he was arrested and declined a plea deal.” He insists he was never a part of the crime and that the man who accused him of it was lying. Sewood has been in prison for 20 years and has seven years left on his sentence.

Hawkins’ wife Anita Hawkins never used to wear makeup, not even mascara. For Anita, “a lot of things happened behind closed doors.” Her parents signed her off as a legal minor when she got pregnant with her son Dakari at age 15. She wrote a book called “The Storm after the Storm” after her own experience with child molestation.

She lived in a worn-down house in Gary, Indiana — a 20-year-old in barber school who cut hair to make spare change for her 4-year-old son. One day, she was called over to Hawkins’ grandmother’s house to cut her hair for Thanksgiving. LaTroy was there. She noticed his even smile and cool demeanor right away.

After talking to Anita for three weeks, LaTroy never mentioned he played baseball. So when he told her that he had to leave for ball camp — well, that was the end of that, she thought. He must be lying.

“Black men don’t play baseball,” she told him.

Anita’s grandma, who was good friends with LaTroy’s grandmother, quickly trumped that suspicion. He proposed three years later on New Year’s of 1999.

Two worlds collided, but not really.

BREAKING FREE

Hawkins almost took a rain check on their ticket out of Gary.

The 22-year-old Hawkins wrestled with consistency at the beginning of his career with the Twins. He gave up an average of 8.67 runs per game in 1995 his first year. Hawkins flew back to Indiana and walked with slouched shoulders to Spectrum, his neighborhood basketball court.

After a few pickup games, one of his high school buddies asked him for two dollars. Two. Hawkins was making about $2400 each month. That was pocket change. But without his bionic arm, he’d be that guy: walking around with his nose to the ground, looking for quarters on the pavement.

Hawkins’ grandfather worked in a steel mill for 36 years and maybe missed four days of work. Maybe. He’d get there an hour before his shift started every day. His grandmother was a nurse. If her shift started at 6 a.m., she’d show up at 4:45. That’s how it worked: If you have a job, if you have a steady income, you hang onto it for dear life.

Hawkins gave his buddy the two dollars and went straight back to Salt Lake City for spring training.

“I thought to myself, ‘Lord knows I’m not goin’ back to Gary, Indiana,’ ” Hawkins said. “I never wanted to be on my hands and knees, beggin’ for two dollars.”

Although LaTroy and Anita have had their share of “this-house-isn’t-a-locker-room”, “why-are-you-wearing-all-that-makeup”, and “I-still-need-your-attention-even-though-you’re-busy” arguments, their two worlds didn’t collide — they orbited with each other. They are the music to the other’s motion. Like how a scary movie isn’t scary until the high-pitched piano song creeps into the background.

Earlier this month, LaTroy was in LA to scout a high school kid for the Twins. The next week, he flew to St. Paul to commentate his first Twins game against the Colorado Rockies, one of his old teams. When LaTroy isn’t busy with work, he and Anita love watching movies and trying out new restaurants.

Anita Hawkins is a model for a “quirky” clothesline called Burning Guitars. She has a bleached buzz cut. She travels to L.A. and New York City and she loves making women feel beautiful by doing their hair and makeup. Her 16-year-old self would have envied who she is now.

Two worlds from the same background, blending into a manifestation of everything they always dreamed of without baseball, and — because of it — they realized.

And then giving it away.

LIVING IN ABUNDANCE

Hurricane Katrina sent families fleeing toward dry land. LaTroy had just gotten traded to San Francisco and Anita was staying at a hotel in Dallas when she saw a young Katrina survivor from New Orleans, balancing a baby girl on her hip and pushing another in a stroller. She was shopping for clothes in the gift shop. Anita offered to watch them while the mother sifted through the sales rack. Something inside her broke.

She knew what it felt like: to be shopping for clothes she needed but couldn’t afford.

Anita called LaTroy. He told her to do whatever she felt was enough. So they bought the mother a new car and an apartment. They still keep in touch with the family.

The couple also sends students to college through the Jackie Robinson Foundation, donates to families in need through Food Pantry, works with an organization that deals with domestic violence and sponsors two homeless organizations. And Anita cuts hair for homeless people in Dallas.

“If you can help just one person… still. It makes a difference,” she said.

Their daughter Troi remembers when the Hawkins flew up to Gary, Indiana, to visit family. They don’t call it the wrong side of Chicago for nothing. Bricks lay on the ground beside crumbling houses, tree branches grew into shattered windows, and most of the local shops were either shut down or looked like they were on the verge of it.

They were driving to the bank when LaTroy saw a man fall off his wheelchair on his way to a bus stop. It was pouring outside, and the man pined for a stronghold on the wet pavement. LaTroy braked in the middle of the road — stopping traffic — got out of the car, and lifted the man back into his chair, pushing him carefully underneath the cover of the bus stop. Troi says moments like that aren’t unusual.

When LaTroy and Anita first married, she was on the phone with Dakari’s biological father, arguing about his involvement in their lives. LaTroy snatched the phone from her.

“You’re his dad. But so am I,” he said. “You have no excuse. We aren’t gonna make you pay child support. We’ll make sure Dakari gets everything he needs financially. If you can’t afford to buy a taxi ride to visit him, we’ll lend you a car. If you live too far away, you can stay with Anita’s mother. We just ask that you’re present in his life. Nothing else.”

It didn’t make a difference — Dakari’s dad never changed. But perhaps that was the point LaTroy wanted to make: Dakari, now, already had a father. Maybe not a biological one, but still. He was always there. One who never left without letting them know where he was going, who never spent his paycheck on alcohol, who — unlike some of his teammates — never compromised his loyalty toward his wife. One who could support him enough financially to send him off to Atlanta and work for a clothing line.

Dakari is still in Atlanta fulfilling his dreams.

Hawkins is like that with both of his kids. Fifteen-year-old Troi is his little girl, but she’s an old soul, like her dad. “She’s too young to be so set in her ways already, but she is,” Anita said.

To his relief, LaTroy doesn’t need to worry about short-shorts. She’s not a girly-girl: She prefers basketball shorts or athletic clothes. She loves hunting, but only with a crossbow. Guns are too easy.

Troi auditioned for a performing arts school in California, and LaTroy sat in the auditorium all day, watching her dance. He’ll probably never be able to distinguish a plie from a releve — let alone recognize the terms — but he was there. When she received the acceptance letter, he wrapped her up.

“I’m so proud of you. You’re putting in work.”

When LaTroy Hawkins compliments you on “putting in work”, you’d better be proud. He, of all people, knows what hard work looks like. He gave up the most earned runs in baseball in 1999. He never started another game in the majors, but he stuck around for 17 more years. He found his niche in closing, saving 127 games throughout his career. Ice in the veins.

The Hawkins recently put their $4 million Texas home on the market so 15-year-old Troi can attend the performing arts school in Burbank, California, in August. She’s an aspiring actress with the athleticism of her dad and modelesque looks of her mom.

Don’t be mistaken: Growing up with a professional athlete as a father was hard. The Hawkins went days, sometimes even weeks, without seeing their dad. As a professional athlete, he’d only come home for 24 hours — if even — before he had to fly back for a game or practice. Troi loved going with her dad to games, but it didn’t happen often. He never let her miss a day of school to watch a game. But in the offseason, he was there. Troi said he’d drop them off at school and — if he could — he’d make it to their games and recitals and science fairs.

Troi does 15-year-old daughter things all the time. When people tell LaTroy he’s got the body of a 20-year-old, she tells him he’s got a belly. She thinks he’s way too overprotective. Like all teen-aged daughters, she admits to not giving her dad enough credit.

Hawkins does annoying dad things all the time. When Troi wants to go to a party, he makes sure he knows the names and phone numbers of the parents. He always needs to know who she’s with and where she’s going. Her curfew is 11 sharp. One time, she walked through the door at 11:03 and Hawkins was waiting. He lectured her on prioritizing her time.

NOT ALL ROOTS WERE PULLED

Anyone watching him commentate on live television can see it, the boldness inside his eyes. He doesn’t hold back. Former minor-league teammate Jamie Ogden can attest: He’s not gonna sugarcoat or downplay a story — he’ll tell you straight-up. He’ll say, on live television, that he got in a fight with former teammate Tommy Kahnle and, when announcer Dick Bremer gives him an out by saying “It was just good-natured, right?” He’ll reply matter-of-factly: “Nope. One of the worst teammates I’ve ever had.”

He’s blunt because, to be honest, he doesn’t really give a rip if people talk about him.

When he threw a wild pitch, or got pulled midway through an inning, or traveled to Boston and heard fans in the bleachers call him the n-word (which wasn’t rare), he felt it no more than he’d feel a mosquito at a bonfire. “A person who doesn’t know me can’t hurt my feelings,” he said.

At least he had heat in his hotel room. At least his wife and kids weren’t falling asleep to Gary gunshots and sirens. At least he could afford to send his little girl to the school of her dreams.

There’s something different about LaTroy. He’s still got his left leg in Gary, Indiana, where his grandpa taught him what 1 Corinthians 13:4 means: to love without expecting anything in return. Without Gary, he wouldn’t drive 50 miles to spend six hours with his little brother in a prison cell while his team is in Michigan. He wouldn’t pay for him to get two degrees while in prison. He wouldn’t fly to California to watch his daughter dance to hip-hop music so loud it shakes his seat. He wouldn’t have befriended the grounds crew and security guards of all 11 teams he played for. He wouldn’t have signed autographs until his wrist hurt.

He doesn’t travel to Gary often, but when he does, he meets with McClain, his high school basketball coach: the one who smacked his behind right out of the place he owes so much to and, at the same time, is thankful to have escaped from. “He never forgot where he comes from,” said McClain.

LaTroy Hawkins broke through the empty beer bottles and eviction notices and high-school dropouts and neighborhood gunshots and broken furnaces where people dropped to their hands and knees for two dollars.

But there’s still a tiny part of the Gary, Indiana, drywall he’ll never break through, and you’ll hear it behind his voice: That’s a good thing.

![Nelson Hall Resident Director Kendall Engelke Davis looks over to see what Resident Assistant Chloe Smith paints. For her weekly 8 p.m. staff development meeting in Nelson Shack April 16, Engelke Davis held a watercolor event to relieve stress. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to really invest and be in [RAs’] lives,” Engelke Davis said, “which I consider such a privilege.”](http://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/041624_KendallEngelkeDavis_Holland_05-1200x800.jpg)