Ken Rohly spends his days teaching chemistry at a private university in Arden Hills, but outside the classroom he has helped develop more than 100 devices for the world’s largest standalone medical equipment company.

By Maddie DeBilzan

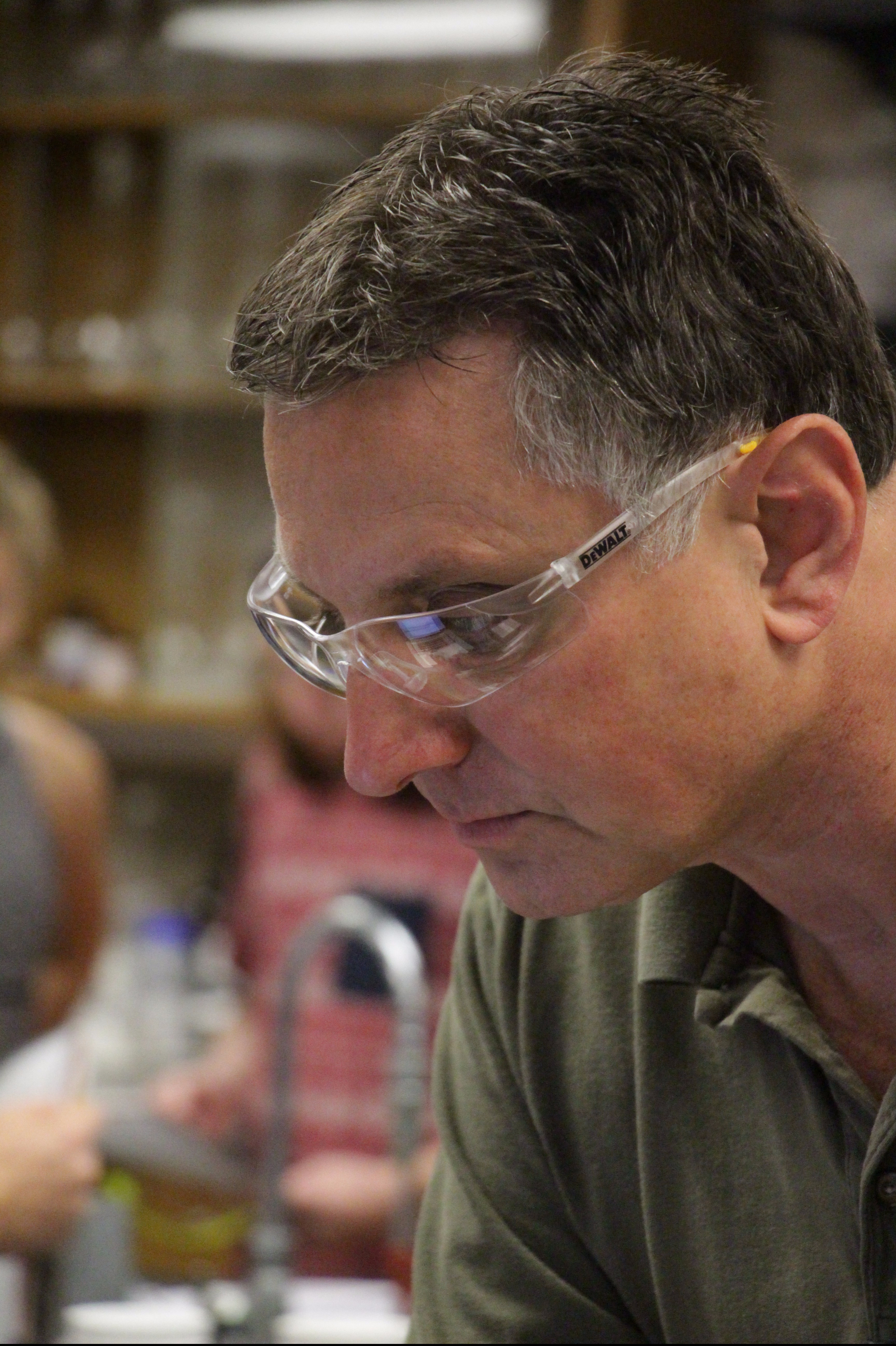

The thing that strikes you most about Ken Rohly is his eyes. They’re the kind of eyes that are unwarrantedly curious. So curious, in fact, they almost make you squirm because, unlike most eyes you see, these ones have wheels turning behind them. They’re the kind of eyes that evoke something that feels like vulnerability out of you. They’re the kind that squint almost incessantly behind wire-rimmed glasses or plastic goggles, because everything is always interesting.

And then there’s his voice. It’s the kind of voice that is smooth and unimposing, but, at the same time, urgent. It screams, “Listen to me: this is important. This formula I’m teaching you, it could save lives someday.” His voice is smooth and even, but not in a boring way, because the questions that come out of his mouth – How can I solve problems that matter? What’s the point of science if it doesn’t help people? Where does God show up in this lab? – beg to be answered. If he were a singer, he’d sound like Frank Sinatra: calm and poised and magnetic and smooth. A voice that demands a listener.

This is a story about a man who likes solving puzzles, who likes taking things apart and figuring out how to put them back together, and – in doing so – has altered dozens of medical prototypes. It’s a story about a curious, soft-spoken man who enjoys the process more than the end result, who gets excited when something breaks, who doesn’t care if he can’t get a thank you from one of the thousands of Americans wearing the tiny squishy object inside their chest, an object in which he spent hours working on, because – to him – it was just an itch he got to scratch. And in the process, he just so happened to keep their hearts beating.

It is mid-morning and Ken Rohly is pulling a pig heart valve out of a glass jar in the basement of Bethel University. He pushes the folds gently as two pairs of student eyes watch in amazement and disgust.

“It’s not every day you see a pig heart in a chemistry lab,” Rohly says.

Especially not at Bethel, the private institution in Arden Hills where Rohly has worked for 30 years.

Rohly is part-time professor, part-time researcher through Medtronic. He’s worked on over 100 products, including the pacemaker, an insulin pump, a blood oxygenator, drug delivery and – his most recent – a dialysis machine, which filters blood efficiently and cost-effectively for people in developing countries such as India, Africa, China, South America and Southeast Asia.

Rohly landed the job at Medtronic about 30 years ago because a friend referred him.

“It’s all about who you know,” he said.

He could find a full-time position at Medtronic, but he doesn’t want one. He could drop Medtronic and focus on teaching, but he doesn’t want to do that, either.

“I feel called to both worlds,” Rohly said.

Right now, he’s got six projects brewing. One of them is an implantable drug pump which helps people with chronic pain. Another is a rechargeable and recyclable kidney care device. Outside of Medtronic, he’s trying to figure out how to extract water from air at a rate of 2,000 liters per day.

The kidney care device, or dialysis machine, is a significant game-changer in global health. When someone’s kidneys stop working properly, usually due to kidney disease, their body has no way of getting rid of contaminants in the blood. The dialysis machine, then, does what the kidneys cannot: it cleans out the blood, allowing that person to continue living.

According to Medtronic, there are approximately 3 million people who suffer from chronic kidney disease worldwide. Over the next 10 years, this number is expected to double.

In developing countries, individuals with failing kidneys have no access to dialysis machines because the devices use too much water and electricity. But the machine Rohly is working on is completely recyclable and portable, which means it can be used in developing countries without drying up resources. Eventually, Rohly said, the machine will start to appear in U.S. hospitals.

He’s been working on the dialysis machine for two years, and – although the first version hasn’t even been released yet – he and Bethel professor Brandon Winters are already starting to work on the second generation, which only uses one cartridge instead of three.

He’s also working on sending a science and technology class to New Zealand on a study abroad trip January 2019, where they will focus on recent scientific developments through the native people of New Zealand as well as study the scientific methods of the colonial era.

Of course, what makes Rohly interesting is that despite juggling six projects, three classes and a study abroad trip, which adds up to between 50 and 60-hour work weeks, he still makes time to watch Sherlock Holmes at night with his wife Cindy. He still is able to go fishing at his cabin on Balsam Lake on the weekends. He still finds a way to make toy cars out of education Legos – which he uses as models for his students – with his grandkids.

And when his kids were young, it was no different. His daughter Amy Gorowski, the lab and safety coordinator at Bethel University, doesn’t remember her dad getting too bogged down in his work.

That’s the thing about Rohly: his actions are always urgent, always purposeful. But he’s never in a hurry.

He’d throw a baseball with his three daughters in the backyard, but methodically. He’d stop them mid-throw and give them step-by-step instructions for the windup. He’d bring home molecular modeling kits and help them build lattice structures. He made them watch Monty Python and cracked jokes like, “You need a haircut? I’ll go get the lawnmower.” And, although he was probably under qualified for the job, he coached his daughters’ youth soccer teams.

Gorowski suffered severe morning sickness from her pregnancy this past summer, right before she and Rohly were supposed to go on a trip to New Zealand and Australia together to develop his 2019 study abroad trip. When she told him she wasn’t sure if she could make it, he was calm – he didn’t push her. So he went alone.

Maybe it’s his analytical mindset that makes him so patient, or maybe it’s his humble confidence. Whatever it is, everyone who knows Rohly talks about it: his even-keeled nature. Wade Neiwert, a professor in the Bethel chemistry department, said that whenever accidents happen in the lab – chemicals spill or glass breaks – Rohly doesn’t even flinch. He just says, “Ok. We’re ok.”

The funny thing is, Rohly said, he wouldn’t consider himself patient in the least. He can only spend a few minutes in Target: he walks in, finds the quickest route to get the things he needs, and walks out. He doesn’t compare prices, he doesn’t scour the aisles for buy-one-get-ones.

In airports, he always speed-walks – even if he isn’t running late.

“I like to think I’m just focused,” Rohly said. “I’m very goal-oriented.”

When chemistry professor Brandon Winters gets frustrated about his research, Rohly just nods his head. “Yep. That’s how it goes sometimes.”

Every once in a while, when he’s standing in his entryway with his shoes on, waiting for his wife Cindy to finish putting on her mascara before dinner, he might tap his feet against the floor and cross his arms – maybe even tell her to hurry up. You wouldn’t catch him raising his voice, though.

He’s so even-keeled that it makes you almost want to yell at him, just so you can see what Ken Rohly looks like when he’s angry. He’s so humble you almost want to shake him just to make him brag, to make him admit to you he’s underrated and underappreciated and incredibly underpaid.

But he wouldn’t, because he doesn’t care about any of that.

He’s happy. He has a brown-eyed wife who’s stood by his side ever since the day she met him at a get-together, when she was a high school track runner and he was a college student who wore too many plaid flannels and striped collared shirts and bell-bottomed jeans.

She was there through it all, even when Rohly was building their house in Lino Lakes and she had to cook dinner in a mobile home parked at a trailer park, shuffling around the space with her husband and three toddlers and two parents.

They each give credit to each other.

“He is very supportive – very kind,” Cindy said, before Rohly cut her off with his quiet voice and opened the door to the basement.

“I don’t need to hear this. I’ll be up in five minutes,” he said.

Cindy continued. “He was just the best father ever.”

He’s got three daughters and two grandkids, with one on the way. He’s traveled to Munich, Budapest, England, Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand and Australia – to name just a few. Most of them were out of sheer curiosity – he simply wanted to see the world. In January, he and Cindy will take Bethel chemistry students to England. He needs her to come because, although he can reason his way out of just about every mystery, he’s still working on the 20-year-old female brain.

Cindy laughed and shook her head. “I’m the mom of the trip, I guess.”

But perhaps the most interesting thing about Ken Rohly is his zeal. He’s still got this fire behind his eyes, the kind you don’t see in people over the age of 20 anymore. He’s not burned out yet – in fact, it seems as if he’s getting more excited about his work. He’s nearing the age of retirement, but he seems more relaxed and passionate than most of his colleagues have ever felt.

He’s teaching a 9 a.m. introduction to chemistry class, and nobody in the lecture is asleep. He’s wearing a striped collared shirt which reads “Lehman Brothers” across the front. He’s writing electron configurations on the chalkboard like it’s the alphabet. Before the students panic, he turns to face them.

“Let’s call this the joy of learning chemistry,” he says – almost sings – in his Frank Sinatra, listen-to-me voice, with his fixed, thin smile.

![Senior Bethel receiver Micah Niewald sheds a would-be tackler on his way to a touchdown in the Royals’ 73-8 win over Augsburg Saturday. Niewald sped his way to two touchdowns in the win, tallying 62 yards after the catch between the two scores. “Knowing I can outrun the guy that’s chasing me is a big thing,” Niewald said. “That’s going back to [strength and conditioning] Coach Meyer and everything we do in the summer and off-season.” | Photo by Carl Schumland, Bethel Athletics](https://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/3J9A1632-1200x800.jpg)