Times have changed for student-athletes and the pressure they face to identify their sexuality publicly; how are NCAA institutions approaching the topic?

by Jared Martinson | Senior Reporter

In today’s society, more and more people are finding their voices to break down barriers and spark the discussion regarding gender and sex. Among those people athletes—high school, college and professional—have opportunities to take stands that not many others have. The collegiate level has been relatively quiet on these fronts compared to high school and professional athletics; recently, student-athletes at higher institutions are making their cases known.

In 2010, George Washington University women’s basketball player Kye Allums came out as the first male-to-female transgender athlete to compete at the Division I level. In 2016, Harvard swimmer Schuyler Bailar announced that he was a female-to-male transgender and that he would be competing for the Crimson’s men’s swim team instead of the women’s team from which he was offered a scholarship in high school. Bailar is the first female-to-male transgender to participate at Division I.

The NCAA’s handbook for “Inclusion of Transgender Student-Athletes” provides definitions for female-to-male (FTM) and male-to-female (MTF) student-athletes desiring to play sports collegiately. Those details are reiterated here.

Trans males are allowed to compete on a men’s team, but cannot be part of a women’s team. However, they must receive a medical clearance for their testosterone treatments, since testosterone is a banned NCAA substance.

Trans females, while receiving testosterone suppression treatment, are allowed to stay on a men’s team if they so choose. They are not allowed to compete for a women’s team until one calendar year of testosterone suppression treatment has been completed.

Any transgender athlete who is receiving hormonal treatment must be “monitored by a physician, and the NCAA must receive regular reports about the athlete’s eligibility according to these guidelines,” as written in the NCAA’s handbook.

If the transgender athlete is not taking hormonal medication, they can only participate on the athletics team “in accordance with his/her birth-assigned sex”.

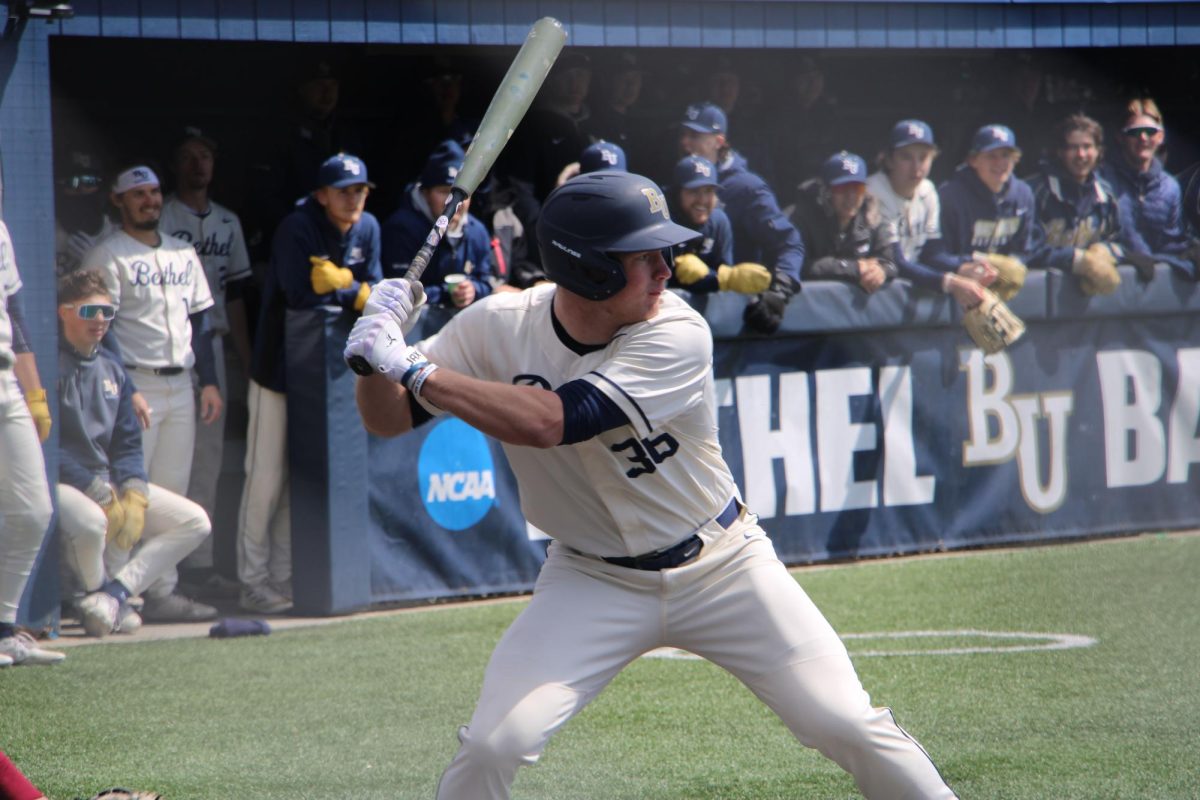

How does this affect Bethel University and other schools with college sports opportunities? The Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (MIAC), of which Bethel is a member, sponsors these NCAA guidelines and recommendations in their own Policy & Procedures Manual. But that’s the arbitrariness of the policies: they are written as nothing more than guidelines. Bethel’s athletics website does not specify any views apart from the NCAA’s inclusion policy.

Most schools across the nation haven’t had to consult these recommendations, as there are very few openly transgender athletes in the NCAA.

![Nelson Hall Resident Director Kendall Engelke Davis looks over to see what Resident Assistant Chloe Smith paints. For her weekly 8 p.m. staff development meeting in Nelson Shack April 16, Engelke Davis held a watercolor event to relieve stress. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to really invest and be in [RAs’] lives,” Engelke Davis said, “which I consider such a privilege.”](http://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/041624_KendallEngelkeDavis_Holland_05-1200x800.jpg)

J C • Feb 16, 2018 at 11:30 pm

“student-athletes and the pressure they face to identify their sexuality publicly”

I don’t see any mention of sexuality in the article other than this. Gender identity is not the same thing as sexuality.

“But that’s the arbitrariness of the policies: they are written as nothing more than guidelines. Bethel’s athletics website does not specify any views apart from the NCAA’s inclusion policy.”

Does the author think there is a specific issue with the guidelines/policies, or that Bethel’s athletics website *should* specify anything in addition to NCAA policy? In the absence of a specific objection with some kind of supporting evidence, this bit doesn’t make sense to me.

Regarding using “transgender” as a noun (e.g. “he was a female-to-male transgender”): this is often considered offensive, and several journalism style guides (e.g. Reuters, BBC) recommend against it.

Robyn Serven • Feb 16, 2018 at 5:20 pm

Allums is female to male transgender.