Clarion articles from decades past shed a unique light on Bethel University’s response to significant events in American history. In past publications, The Clarion has released several articles surrounding the issue of race and diversity on campus. The conversation started shortly after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968 and has continued into the present.

By Emma Harville

Martin Luther King Jr. accepted an invitation to speak at Bethel College in the winter of 1960, 10 years before the first Black student would step foot on campus and 60 years before George Floyd would die under the knee of a white Minneapolis police officer.

Although MLK was unable to attend the convocation because of scheduling conflicts, President Carl Lundquist invited MLK because the faculty had felt a “keen sense of personal concern” regarding racial equality, which Lundquist wrote in his first letter of correspondence with MLK in 1957.

Floyd’s death has fueled a social justice movement for Black Americans throughout the nation, and for allies throughout much of the planet. Now MLK’s words decorate social media feeds and flowers line the intersection of 38th and Chicago because people have realized their silence is not, and has never been justified.

The riots, the protests, the demands for justice – they remind me that Bethel University, while making progress toward welcoming a more diverse community, has a deep-rooted history of white homogeneity.

Today is Juneteenth, which marks the day in 1865 when enslaved Africans in Texas not only learned they were free, but that the Emancipation Proclamation had set them free more than two years prior. Many Americans do not know their own country’s history, just as many Bethel students are not aware of their own school’s history with racism and discrimination.

Bethel College was established in 1871 by a cohort of Swedish Baptists. The first handful of Black students did not enroll until nearly 100 years later in the fall of 1970, after the assassination of MLK prompted faculty to create a “Minority Recruitment Committee.”

Based on Clarion stories I’ve found from the last 60 years, the deliberate recruitment of Black students at Bethel in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement seemed like a gesture more rooted in the institution’s self-interest, yet disguised as an act of Christian love and acceptance.

In a 1969 Clarion article, chairman of the Minority Recruitment Committee Jon Fagerson argued that racial discrimination could be “overcome” by encouraging minority students to come to Bethel and that it would “also give the opportunity to evidence our Christian convictions and love” while “reliev[ing] the guilt feelings that some experience” from playing a part in racism.

But once the first Black students arrived on campus, they faced pushback from the white majority, as seen in the archives. A 1975 Clarion article cited allegations that Black students had been allowed into Bethel with lower academic standards, that they’d been given a “free ride” financially and that they were exempt from signing Bethel’s statement of faith.

None of the allegations were true, according to Jim Bragg, the director of College Relations at the time.

In a 1970 letter to the editor, a student named Doug Warring called for the end of “preferential treatment” for Black students, calling minority recruitment “anti-Bethel” and stating Black students who claimed to be mistreated were “not portraying the accepted ‘Bethel Image’ as handed down by faculty and staff directives.”

“Some Black students who are receiving much from Bethel have been screaming ‘discrimination’…If anyone does not like the current system and cannot improve or exist under its present structure, he should leave this institution to those who wish to keep it intact by calmly dismissing himself,” Warring wrote.

Professor of New Testament Robert Stein also wrote a letter to the editor in 1970, in which he wrote: “I personally believe that neither Bethel College nor I are guilty of being ‘racist’ by definition. We have not as an institution rejected minority students who have applied simply because of their being Black.”

I am afraid many white students at Bethel today have had the same defensive mentality Stein did: “I’m not racist because I would never discriminate against someone based on their skin color!”

The problem with such a mentality is that it ignores a simple truth: Any white student who succeeds at Bethel has done so because the system was designed for them to succeed.

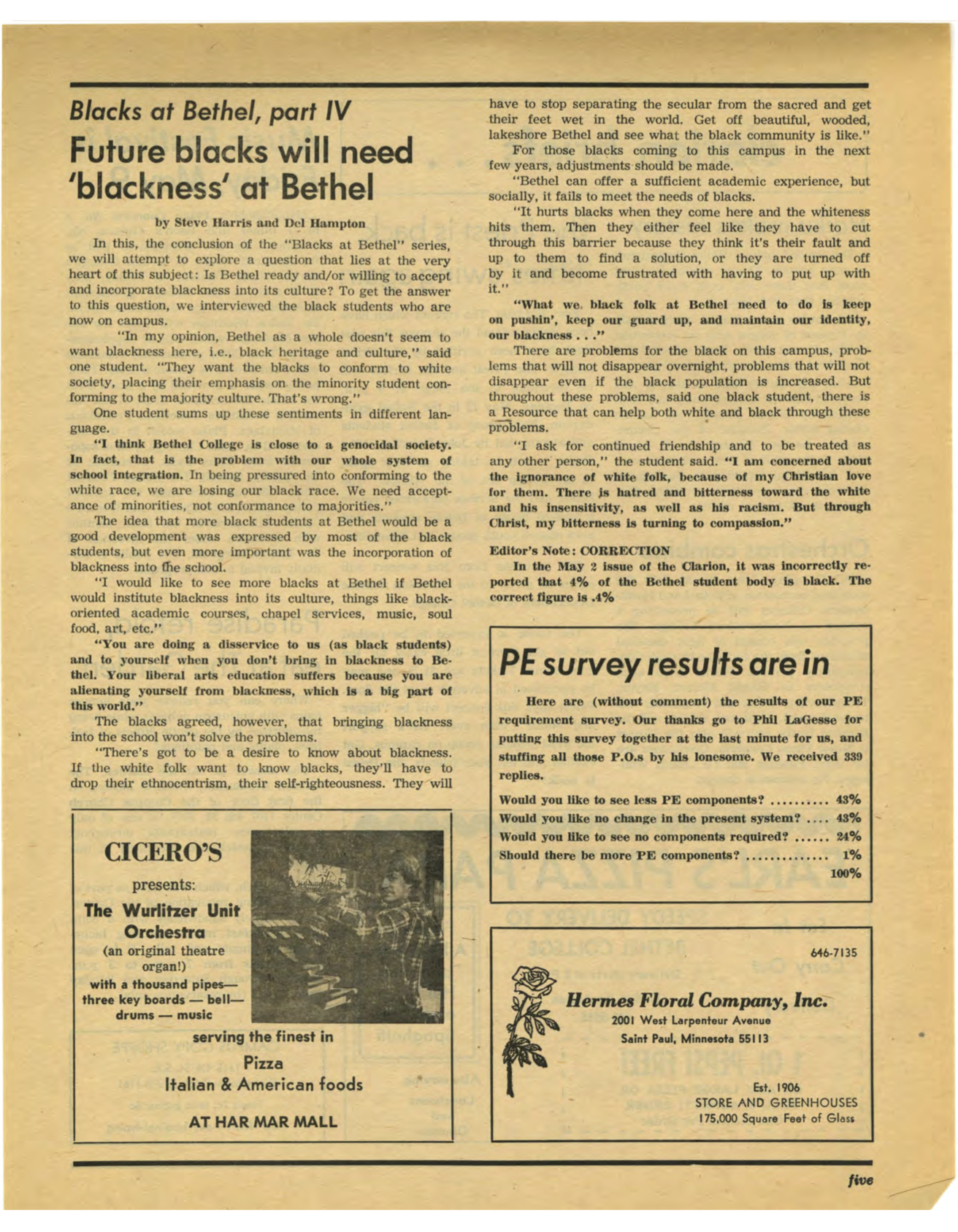

When The Clarion article below was published in 1975, Black students made up 0.4 percent of the student body. Today, that number has risen only to 3 percent of the CAS student population, according to institutional data as of 2018-19.

I reached out to Del Hampton, the former Black student who was given writing credit on this article decades ago, and asked him to read it over.

He said he doesn’t remember much about the article itself but recognized a quote about Bethel’s expectation of Black students to conform to its white Christian culture as “something I would, and still, say.”

“I actually find it amazing how much of what was said then is still relevant now in society, 45 years later,” he wrote back to me. “Oh, how little we have learned, better yet changed.”

More than a decade after Hampton’s story, a Black student named Peter Knight shared similar grievances in a 1988 letter to the editor, alleging he’d heard both Bethel students and professors utter the n-word in the classroom with “ease.”

“I have found out that no matter how friendly I am, some people will never accept me as an equal,” student Eli Escobar wrote in a letter to the editor, also in 1988. “The problems this school has will find a way to come out soon.”

In 1991, Director of Security Bill Watson found the words “Die, n––” written on a notepad left outside his door, according to a 1992 article. Throughout the next month, skull and crossbone drawings showed up on the same pad. The harassment didn’t end until a hidden camera caught the offender in the act.

One Black student found a dead fish in her P.O. box, the article also reported. Other Black students said they were carded in the cafeteria during lunch while white students were not.

Hate mail and harassing phone calls were a “regular occurrence” for Black students during these years, Director of Multicultural Development at the time Terry Coffee added in the same article.

A 1992 article reported that a student belonging to a northeast Minneapolis white supremacy group confronted Black social work professor Nicholas Cooper-Lewter in his office, threatening him and telling him he wanted Bethel to return to its “Christian white right.” The student had to be forcibly removed from Cooper-Lewter’s office by security and was later expelled.

United Cultures of Bethel, a club we know today as dedicated to supporting students in their cultural identities, was formed that year.

In the spring of last year, I wrote a story titled “Transforming Bethel’s DNA” as part of a themed issue about Bethel’s identity. I listened to two Black students, both UCB members, echo sentiments nearly identical to those found in these decades-old articles, including the one above from 45 years ago.

One told me she’d jokingly been called a slave by her lab partner freshman year. Another told me she’d been alienated on her dorm floor after someone falsely accused her of stealing a piece of clothing.

While the testimonies of these students do not represent the entirety of the experience of Black students at Bethel, these stories are enough to prove a pattern of intolerance and bigotry that continues to rear its head in spaces deemed “accepting.”

I do not want to discount the relentless work and dedication many faculty members and community leaders have put in to making Bethel a more welcoming space for all students in the past several years. However, I know we still have a long way to go. And I know they know that, too.

I’ve heard many of my white friends at Bethel claim politics just “aren’t their thing.” If you’re not planning to vote in the upcoming election because you “don’t know anything about the candidates,” consider that maybe you come from a place of privilege that allows you to not worry about these policies directly impacting your life. Not all Bethel students have that luxury.

All students, especially those white students who claim to exemplify Christian love and acceptance, should know Bethel’s history in order to understand why we as a nation have reached this crucial tipping point.

Because of this, The Clarion plans to run an in-depth series during the upcoming school year that examines how our white Christian culture has been used as a tool for oppression, exposes the ugliness of Bethel’s (at times) racist past and reminds us of the tiresome work that’s still ahead. And let us not forget, this is work we must all take part in.

I invite all Bethel students to offer The Clarion ideas on what should be included in such a series or input on public events the newspaper could sponsor to increase cultural awareness and education on our campus.

And then there’s just one thing left to do, as the 1975 Clarion article stated above: “Drop [your] ethnocentrism, [your] self-righteousness… Get off beautiful, wooded, lakeshore Bethel and see what the Black community is like.”

A previous version of this column stated that Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Bethel College in 1960. While MLK was indeed scheduled to speak in a convocation series at Bethel, The Clarion found a letter from President Carl Lundquist which stated MLK was unable to come to Bethel due to scheduling conflicts.

All historical information in this article has been pulled from The Clarion archives, which can be accessed through the Bethel University Digital Library.

![Nelson Hall Resident Director Kendall Engelke Davis looks over to see what Resident Assistant Chloe Smith paints. For her weekly 8 p.m. staff development meeting in Nelson Shack April 16, Engelke Davis held a watercolor event to relieve stress. “It’s a unique opportunity to get to really invest and be in [RAs’] lives,” Engelke Davis said, “which I consider such a privilege.”](http://thebuclarion.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/041624_KendallEngelkeDavis_Holland_05-1200x800.jpg)

Kent Gerber • Jul 8, 2020 at 11:07 am

I look forward to furthering this discussion at Bethel and thank you for writing it. The purpose of the Timeline exhibit in the Clarion collection was to surface and further this very conversation. Rich, this article is correct and is based on the findings of investigations from Diana Magnuson, Carole Cragg, and myself. The items that the author bases their research upon were a result of these investigations and discoveries. Dr. King did not speak at Bethel because of increasing unrest in Atlanta, Georgia when he was scheduled to come. Diana Magnuson and I wrote up what we found when she and the librarians investigated this claim. As a result of these questions, Carole Cragg located the letters of Carl Lundquist located in a Stanford Library collection and I negotiated with Boston University to add the copies to our collection. Here is the article published in the June 2011 issue of the Baptist Pietist Clarion (archived in the Bethel Digital Library). See page 7 for the beginning of our article – https://cdm16120.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/beunhisco/id/1309

Kent Gerber, Digital Initiatives Manager, Bethel Library

Richard Sherry • Jun 20, 2020 at 8:58 am

Did King in fact speak on the Bethel campus? You should ask Diana Magnuson, who has been our archivist. There was discussion about this some years ago, and the general consensus was that the announcement was made and then either that Dr. King chose to withdraw or was unable to attend.